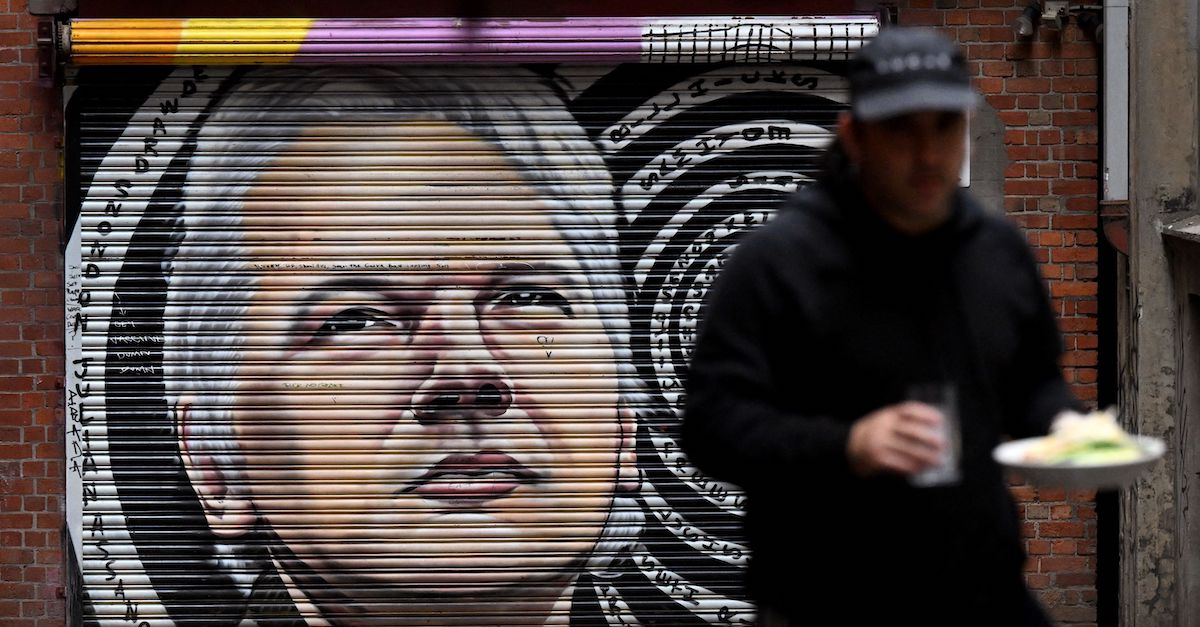

People walk past a mural of Julian Assange in a Melbourne inner-city laneway on June 20, 2022.

Listen to the full episode on Apple, Spotify or wherever else you get your podcasts, and subscribe.

After the United Kingdom formally approved the extradition of WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange, First Amendment groups in the United States expressed broad opposition to his prosecution, but U.S. prosecutors accuse him of conduct that goes well beyond publishing classified information.

In a 49-page superseding indictment, prosecutors say Assange conspired to break into a U.S. military database, gained unauthorized access to an Icelandic government computer, and chose targets for hacker collectives to breach.

The bulk of the 18 charges, however, accuse Assange of violating the Espionage Act by publishing of secret information leaked by former U.S. military intelligence analyst Chelsea Manning.

Those are the allegations that prominent First Amendment advocate Jameel Jaffer calls a “dagger to the throat of press freedom.”

“The central point to those charges is that Assange published classified information, and literally every day, news organizations in the United States published classified information,” said Jaffer, the director of Knight First Amendment Institute at Columbia University. “So if you allow Assange to be prosecuted and convicted for these things, what’s to stop the U.S. government—this administration or the next administration—from bringing similar charges against more conventional news organizations.”

On the latest episode of Law&Crime’s podcast “Objections: with Adam Klasfeld,” Jaffer fields questions about some of the toughest criticisms of Assange, from U.S. prosecutors and others, and says that in the end, the case is about more than just him.

For the most part, Jaffer’s concern about Assange’s prosecution relates to the Espionage Act, a more than 100-year-old law enacted shortly after World War I.

“In general, I think people think of the Espionage Act as a statute that is or should be used against spies,” Jaffer noted. “After 9/11, the Bush administration began using the act, not against spies, but rather against government insiders who leaked information to the press.”

Barack Obama’s administration dramatically ramped up its use in the age of mass leaks, including against Manning, Edward Snowden, John Kiriakou and others. Though Obama’s DOJ deployed the Espionage Act more than all of his predecessors combined, it was the Trump administration’s Justice Department that indicted Assange, whose case has carried over into Joe Biden’s administration.

Jaffer said Assange’s case marks the first time it was used against a publisher.

For Jaffer, the other allegations against Assange spark less of a concern, including the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act.

“The charge here is that Assange helped Chelsea Manning hack into a government database,” Jaffer noted, playing down the allegations as “murky or weak.”

Prosecutors concede that Manning had authorized access to the database in question but would have been easily tracked on her account. Assange allegedly tried to crack an “encrypted password hash” in order to enable Manning to exfiltrate files without detection, actions that WikiLeaks defenders play off as extreme source protection.

READ RELATED: Judge Refuses to Pause on Trump v. Clinton RICO Hearing

The indictment also says WikiLeaks helped Snowden flee prosecution, ultimately winding up in Russia.

At least twice in the indictment, Assange’s allies with the hacker group LulzSec, an offshoot of Anonymous, allegedly target news organizations. The description of the breach of an unidentified TV network for an unflattering documentary matches previous reports of an attack on PBS.

On Feb. 21, 2012, Assange allegedly told LulzSec’s co-founder—Hector Xavier Monsegur a.k.a. Sabu—that the “most impactful” leaks would be from the CIA, NSA, or the New York Times, according to the indictment.

Jaffer agreed that prosecuting those who attack news organizations, in principle, is in the interest of press freedom.

“If Assange hacked into either government databases or private databases, or helped others hack into government databases, or the New York Times database, then prosecute him for it,” Jaffer said. “I’m all for it. I am not here to say that Assange is immune from criminal prosecution for anything he may have done. My concern is with the charges that the government has actually filed.”

Assange’s branding as a press freedom icon has lost some of its luster in the decade since Manning’s leaks laid bare hundreds of thousands of Iraq and Afghanistan war logs, U.S. diplomatic cables, and Guantanamo Bay prisoner profiles.

The WikiLeaks founder has not been charged to date with conduct related to the publication on Democratic National Committee emails in 2016, by what the U.S. government has identified as Russian military intelligence operatives. Assange falsely insinuated that the source of the leaks was murdered DNC employee Seth Rich, a claim denounced by Rich’s parents and debunked by the timeline.

In an alarming report published by The Atlantic, WikiLeaks’ official account suggested to Donald Trump Jr. that his father not concede the 2016 election if he lost. Trump won that year, but he threw U.S. democracy into turmoil by refusing to do accept his defeat the next cycle. The report prompted questions about Assange’s relationship to autocracies and self-professed democratic bona fides.

Jaffer urges observers to remove their perceptions of Assange from the equation and focus on precedent.

“The question here isn’t, ‘Is Assange a nice guy who has ever done anything wrong?’ ‘How do we feel about him?’ The question, at least for anyone who cares about press freedom is, ‘What are the implications of allowing the government to pursue this prosecution on the basis of the indictment that it has brought?’ And once you consider it through that lens, the whole thing starts to look pretty chilling.”

Assange is appealing the extradition decision.

Listen to the full episode, below:

(Photo by WILLIAM WEST/AFP via Getty Images)

Have a tip we should know? [email protected]

Source: