People living in some areas of Britain are three-times more likely to be living in poor health than those in other parts of the country, a report reveals.

Researchers say there is a ‘stark divide’ in health and wealth nationally – and often the ‘double injustice’ of the least well-off also being the sickest.

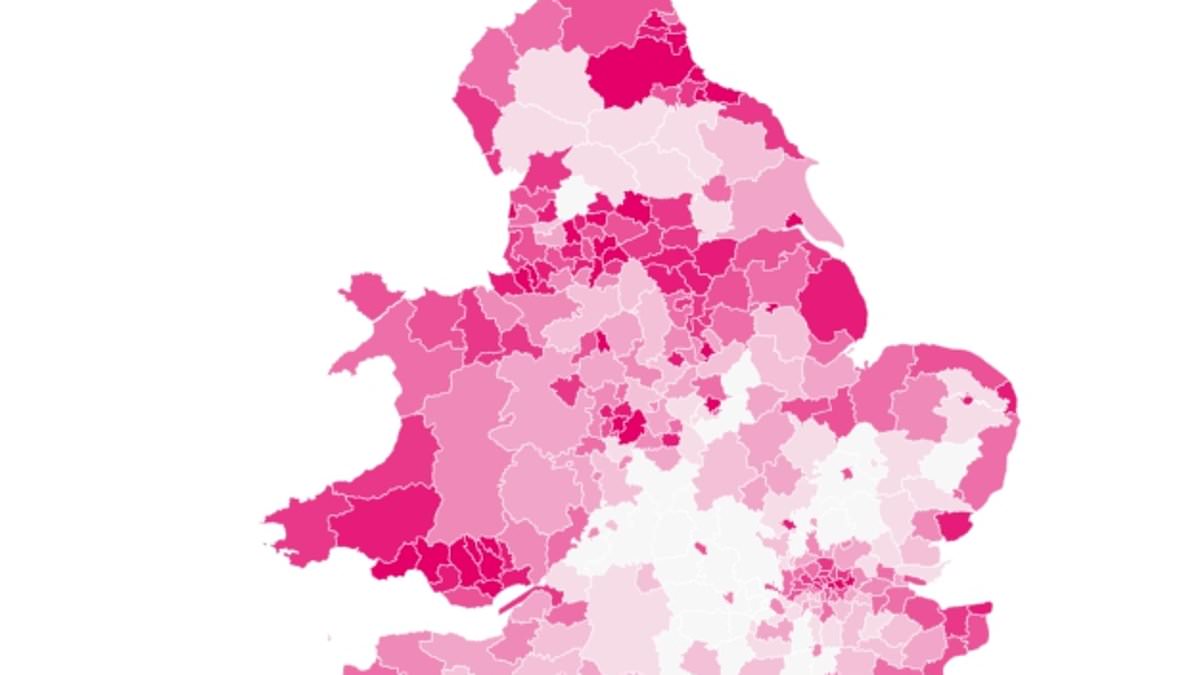

The Institute for Public Policy Research analysed data across England and Wales to highlight the ‘bad health blackspots’.

It found sickness and poor health is clearly linked to low productivity, high poverty and persistent unemployment.

Notably, one in every four people who are ‘economically inactive’ live in just 50 of the 330 local authorities examined.

People in Liverpool are almost three times more likely to be in poor health than those in Oxfordshire, and twice as likely to be out of work and not looking for employment or in full-time education.

Overall, people living in the most deprived parts of the country are more than twice as likely to be in poor health as those living in the most affluent – and are around 40 per cent more likely to report economic inactivity.

The most recent data from the Office for National Statistics (ONS) shows the economic inactivity rate for those aged 16 to 64 is 20.8 per cent – the equivalent of 8.7 million people.

The IPPR found northern cities and their surrounding areas, Midlands cities, coastal cities and rural places had the lowest levels of life expectancy and years of good health compared with more affluent places.

It also found higher numbers of people in receipt of personal independence payments, lower overall wealth, lower household income per head, worse early years development scores and lower rates of NVQ4+ qualifications.

When looking in detail, one in every 10 people in places such as Liverpool, Manchester and Nottingham reported bad health, compared with around just one in 33 in Hart in Hampshire, West Oxfordshire and South Oxfordshire.

Overall, 34 per cent of working age people in Liverpool and Manchester are economically inactive, while the figure is 39 per cent in Nottingham.

The report said ‘having a good job’ is good for both mental and physical health, and cuts the risk of early death.

However, it warned that work no longer offers a reliable route out of poverty, with 68 per cent of working age adults in poverty living in a household where at least one adult is in work.

Meanwhile, even in homes where two people are in full-time work, the risk of falling into poverty has more than doubled in the last 20 years (from 1.4 to 3.9 per cent).

The highest levels of in-work poverty were found in London, Wales, and the north of England, the report said.

To help fix the problems, the study recommended a framework called Seven for Seven, which sets out the foundations for healthy lives – including healthy bodies, a safe home, a great start to life and freedom from addiction.

The IPPR also wants to see new health and prosperity improvement zones (HAPI), with powers to invest, raise local taxes and set missions in the worst-affected areas.

For example, more power could be given to regional mayors so they can introduce local taxes on things such as alcohol, junk food and tobacco.

A recruitment drive is also needed for public health specialists, alongside the creation of new local apprenticeship opportunities and establishing a national health volunteering service, the report said.

Professor Donna Hall, IPPR commissioner and former chief executive of Wigan Council, said: ‘People working within local government and health services are trapped by a lack of resources, support and agency to serve their local population. People feel unheard and their health is suffering.

‘The new HAPI zones would serve as an innovative response to growing poverty and ill-health, put power into the hands of local leaders and ignite local ownership over the future of public health.’

Efua Poku-Amanfo, research fellow at IPPR and lead author of the report, said: ‘The case for Government spending and action on health is clear. It’s not just the morally right thing to do, it’s the economically sensible thing to do.

‘Bad health blackspots, especially in the north east and north west of England and the south of Wales, are stifling national economic growth and holding back the wealth and health of the nation.’

A Government spokesman said: ‘We are committed to increasing healthy life expectancy by five years by 2035 and narrowing the gap between local areas by 2030, including by investing up to £14.1billion to improve health services and help people live longer, healthier lives.

‘Our Major Conditions Strategy will look at the prevention and management of conditions responsible for over 60 per cent of ill health and our plans for a smokefree generation will make a significant difference, with people in more deprived areas almost twice as likely to die for smoking-related conditions.

‘Our Back to Work Plan will also help up to a further 1.1million people to look for and stay in work that’s suited to their needs including through integrated mental health support such as NHS talking therapies.’