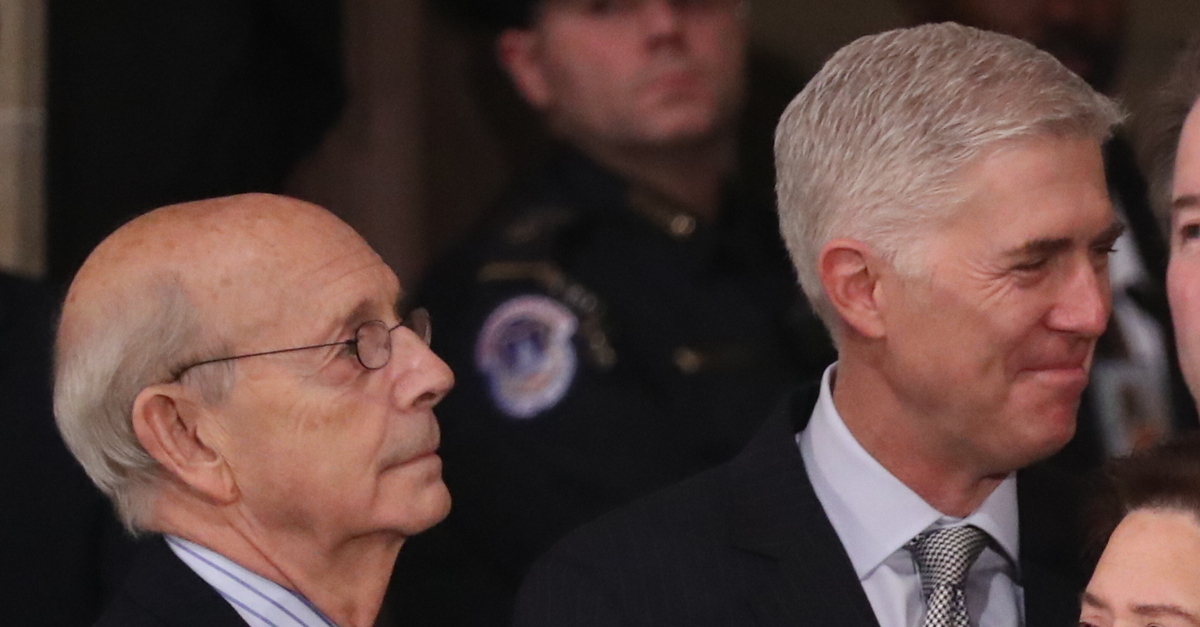

Associate Justices Stephen Breyer (left) and Neil Gorsuch (right).

The U.S. Supreme Court on Tuesday heard oral arguments in a case about a veteran’s disability benefits that were denied because the government misread and misapplied a federal law for decades.

In the case stylized as George v. McDonough, Justices Neil Gorsuch and Stephen Breyer offered extreme skepticism of the government’s perspective but seemed to be in the minority as the only strong and consistent voices in favor of the petitioning veteran’s position.

The petitioner, Kevin George, enlisted in the Marines in June 1975. Prior to the start of his military service, George underwent a standard medical evaluation which produced no abnormal findings. A week after enlisting, George suffered a psychotic episode, was hospitalized, and was diagnosed with paranoid schizophrenia. At the time, the VA’s Medical Evaluation Board found that George’s condition existed before his military service, but that his service aggravated the condition. George was then discharged from the Marines in September 1975.

The following December, George filed for disability compensation seeking service-connected aggravation of his schizophrenia. In 1977, his claim was denied on the basis of a VA regulation that allowed the department to tidily dispense with such claims by arguing that a veteran was sick before enlisting. That regulation, however, didn’t follow federal law, which required compensation for sicknesses aggravated during service.

In 2003, the VA regulation that had been applied in George’s case was deemed unlawful by the Federal Circuit on the grounds that it conflicted with the statute. George then filed a motion requesting his denial be revised as it had been based on the “clear and unmistakable error” of having applied a regulation that conflicted with the law.

Two lower courts–the Veterans Court and the Federal Circuit–sided with the VA on the grounds that the agency applied the regulation in existence at the time. In his petition for a writ of certiorari, George argues that under the law, he is entitled to disability compensation.

“What the agency did here could not even colloquially be called an interpretation,” George’s attorney Melanie Bostwick argued on Tuesday. “VA’s presumption of soundness regulation tracked the statute most of the way and then simply lopped off the end of the sentence, eliminating the second half of the VA’s two-part obligation.”

While the basic question about what the VA did in George’s case was not an issue of particularly hot debate, a majority of the court appeared skeptical of the veteran’s efforts to win what would amount to a substantial monetary judgment in his favor.

Justice Clarence Thomas and Chief Justice John Roberts appeared to endorse theories advanced by the government that the 2003 decision, in a case stylized as Wagner v. Principi, was more akin to a change in law–which would foreclose against a retroactive effect.

Justice Samuel Alito accused Bostwick of “trying to make this a lot simpler than it is” and suggested the nation’s high court was struggling to decide which side’s version of the kind of “error” that occurred was more persuasive and controlling in the case.

“What petitioner is suggesting is a real radical change here,” Anthony A. Yang, arguing for the Secretary of Veterans Affairs, said.

To hear the government tell it, the alleged error that should be examined is what the adjudicatory board did. But, Yang argued, since the regulation, later changed, was on the books at the time George was denied benefits, the board didn’t actually make an error at all.

Gorsuch was unconvinced by every argument Yang put forward.

“We don’t normally think of judicial interpretations as changes in law,” the textually-inclined justice said, citing an amicus brief filed in the case, before shifting to a hypothetical example that left nothing to the imagination about how he viewed the government’s perspective here.

“We have a regulation that’s clearly wrong,” Gorsuch said after tussling with Yang and raising his voice as the two talked over each other. “Let’s say the regulation, since you want a regulation, says that a certain standard of disability applies in a segregated army differently based on race. That couldn’t qualify as a clear and unmistakeable error?”

“No,” Yang said, while insisting that there might be other ways to correct such a regulation.

Gorsuch interrupted to rephrase the question and put it in direct line with the facts of the present case. Yang responded by citing to part of the petitioner’s brief which prompted another interruption.

“I understand that,” the justice said. “That’s not my question, though. And you know it’s not my question. My question is: could a later court correct that or not?”

After some back-and-forth, Yang again conceded that a court could not go back and correct the segregated army benefits question “under collateral review.”

“So, we agree that that error could not be corrected, that that would not be qualified as a clear and unmistakeable error on your account,” Gorsuch replied. “It’s a remarkable claim.”

In terms of potential relief for George, however, Gorsuch was decidedly less committal.

READ RELATED: Who Is Adam Chowdhary From Hale Barns? Know About His Family As Yousef Makki Murder Documentary Airs

“Do we have to reach the question of remedy, or could we remand it back at the federal circuit to decide what the remedy would be?” he asked Bostwick, who responded that a remand would be proper. In the end, the justice appeared ready to issue an opinion saying the federal circuit parsed the question incorrectly.

Breyer, for his part, was clear that the real question was about money and said the issue before the court was clear and “easy.”

He offered an example of a statute that authorizes $1,000 for every veteran of World War II or Korea. In this example, the agency’s regulation leaves off Korean veterans.

“The fact that they have to follow the reg does not absolve them,” Breyer insisted during his softball questioning of the veteran’s attorney. “This is a natural way of talking about things.”

“How did they ever not copy those last six words?” the outgoing justice asked out loud at one point, musing as to whether there’s any other case in existence where the regulation writer left off a great deal of the statute–while leaving open the possibility that the government could cite such a case.

But when Yang was questioned by Breyer, no such case was cited. And the justice was quite loud, almost shouting, and animated in his calculated perplexity directed at the government.

“This is the most clear and unmistakeable error I’ve seen in 40 years,” Breyer said when questioning the VA’s attorney. “I can’t think of another one.”

“Very simple.” the justice continued. “[The VA] had no reason for not writing it into the reg. Even the government with its tremendous resources…has not been able to find a reason why they would have left that out. It was an accident. But it’s sure clear. And it’s sure unmistakeable.”

Justice Elena Kagan, while adamant that the adjudicatory board made the right call based on what was in front of them, offered a what appeared to be a representative version of the question as the majority of the court saw it when questioning the VA’s attorney.

“Just assume that the regulation was clearly an unmistakably wrong,” she instructed Yang. “Now the question is: is the decision based on that regulation clearly and unmistakably wrong?”

“The board did nothing wrong here,” Kagan continued. “But the VA as a whole…did do something wrong. Why is the focus on the board’s decision rather than the VA decision-making as a whole?”

Justices Brett Kavanaugh and Amy Coney Barrett didn’t reveal much about their understanding of the merits but both seemed a bit taken aback by potential floodgates being opened with a favorable ruling for George that might see a large number of veterans able to recoup benefits previously denied under the old, mistaken understanding of the law.

In the end, Justice Sonia Sotomayor also appeared to lean toward Gorsuch’s perspective, saying “we have the government confessing error, saying, please invalidate our regulation, it’s wrong” and saying the government had very little textual support for its position. Her questioning, however, less obviously embraced George’s position and was not nearly as combative with the government’s position as either Breyer’s or Gorsuch’s.

“I don’t understand how you can claim that clear and unmistakeable error, in the decision made, in the statute, in the interpretation of the statute–even if it was compelled by the regulation at the time–is disjunctive,” she said, eventually leaning toward the petitioner. “Error in the statute, or error in the regulation. This is an error in applying the statute. So, why isn’t that clear and unmistakeable or potentially clear and unmistakeable?”

Gorsuch again offered a clear indication of how he was leaning as the government attorney’s time at the dais drew to a close:

The adjudicatory body has two options: one, follow a law that’s pretty clear on its face and is inconsistent with the regulation, alright? Another law that says follow the regulations. It has to choose. I don’t fault it. It chose one rather than the other. It might in some sense be understandable. Justified maybe even? But why can’t that fairly be described as ‘clear and unmistakable error’ to the extent that it rests on, its analysis depends upon, a clear misinterpretation of the statute?

On rebuttal, Bostwick pointed out that veterans were not allowed direct review of their cases until 1988. She also sought to clarify the definition of clear and unmistakeable with a VA definition from a 1956 regulation that identified the phrase to mean “obvious or manifest.”

“That’s exactly what we argue it means in the clear and unmistakeable error context as well,” she concluded.

Elura Nanos contributed to this report.

[image via Jonathan Ernst/Pool/Getty Images]

Have a tip we should know? [email protected]

Source: