Richard Bernard Moore appears in a South Carolina Department of Corrections mugshot.

An inmate on death row in South Carolina has chosen to die by firing squad, according to court records filed Friday and obtained by Law&Crime. Richard Bernard Moore made the selection while arguing that his two allegedly available choices, a firing squad and the electric chair, are both unconstitutional — and as his lawyers continue to fight to save his life.

State prison officials previously notified Moore that a third option prescribed by state law, lethal injection, was not available.

A full statement filed by the convicted killer reads as follows:

I, Richard Bernard Moore, am challenging the legality and constitutionality of the firing squad and electric chair in an ongoing action in the Richland County Court of Common Pleas. Owens, et al. v. Stirling, et al., No. 2021-CP-40-02306. By operation of the state’s method-of-execution statute, which is also challenged in that action, the Department of Corrections is today forcing me to elect my method of execution. The Department is presenting only the firing squad and electrocution as the available methods from which I can choose. If I decline to make a choice, the Department intends to execute me by electrocution.

I do not believe or concede that either the firing squad or electrocution is legal or constitutional. I do not believe the Department should be allowed to certify that a statutorily prescribed method, such as lethal injection, is unavailable without demonstrating a good faith effort to make it available. However, I more strongly oppose death by electrocution. Because the Department says I must choose between firing squad or electrocution or be executed by electrocution I will elect firing squad.

I believe this election is forcing me to choose between two unconstitutional methods of execution, and I do not intend to waive any challenges to electrocution or firing squad by making an election.

Moore made the selection after the state notified him that technically three options were available.

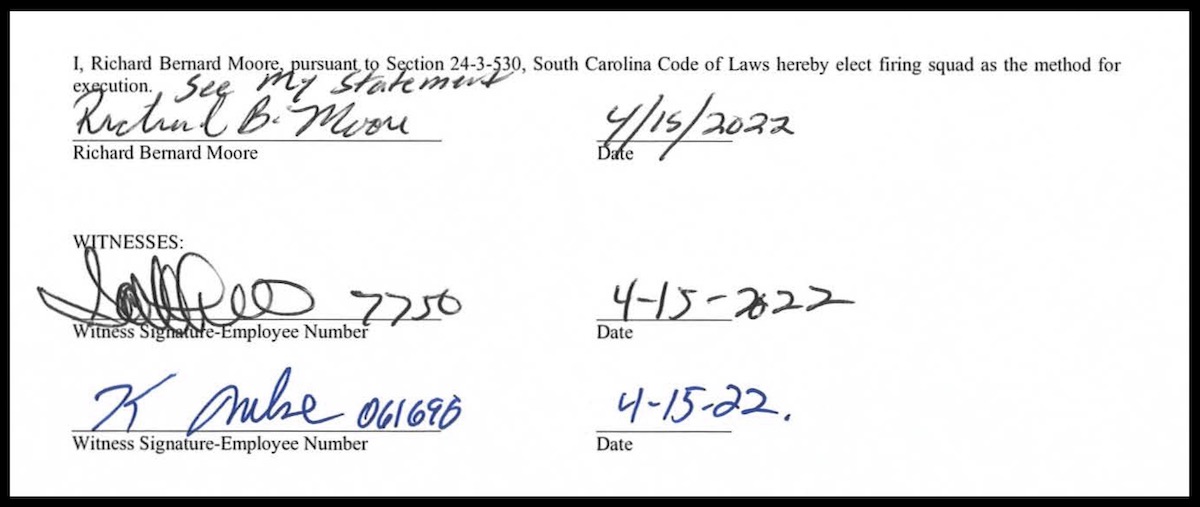

Death row inmate Richard Bernard Moore’s signature appears on a “notice of election” form filed in court. Moore directed the courts to a separate, typewritten statement that was attached to this form — a document which also bears his signature.

According to a letter signed by Moore, the state’s policy is as follows:

A person convicted of a capital crime and having imposed upon him the sentence of death shall suffer the penalty by electrocution or, at the election of the convicted person, by firing squad or lethal injection, if it is available at the time of election, under the direction of the Director of the Department of Corrections. The election for death by electrocution, firing squad, or lethal injection must be made in writing fourteen days before each execution date, or it is waived. If the convicted person receives a stay of execution or the execution date has passed for any reason, then the election expires and must be renewed in writing fourteen days before a new execution date. If the convicted person waives the right of election, then the penalty must be administered by electrocution.

Attached to that basic promulgation was an affidavit by Bryan P. Stirling, the director of the South Carolina Department of Corrections (and former chief of staff to former Gov. Nikki Haley). The affidavit indicated that of the three options contemplated by S.C. Code Ann. § 24-3-530, only two were available:

I hereby certify that, as of April 8, 2022, the only statutorily approved methods of execution available to the Department are electrocution and firing squad.

Despite diligent efforts, the Department has been unable to obtain or acquire the necessary drugs for execution by lethal injection.

The Department’s efforts have included contacting manufacturers, all of which have refused to sell the drugs to the Department. The Department has also contacted various compounding pharmacists regarding compounding the drugs for the Department, but those efforts also have been unsuccessful. Additionally, the Department has attempted to purchase the bulk components for the drugs and have them compounded, and those efforts have likewise proven unsuccessful.

As a result, lethal injection is not available to the Department as a method of execution.

According to a 2004 South Carolina Supreme Court case, Moore was convicted of shooting which occurred Sept. 16, 1999, during an armed robbery at a “convenience store on Highway 221 in Spartanburg.” The state’s version of the events — the version the jury believed — differs starkly from separate claims made by the defendant some seven years after his trial. Here’s the version that the Supreme Court considered during the 2004 direct appeal:

According to Terry Hadden, an eyewitness, Moore walked into Nikki’s at approximately 3:00 a.m. and walked toward the cooler. Hadden was playing a video poker machine, which he did routinely after working his second shift job. Hadden heard Jamie Mahoney, the store clerk, yell, “What the hell do you think you’re doing?” Hadden turned from the poker machine to see Moore holding both of Mahoney’s hands with one of his hands. Moore turned towards Hadden, pointed a gun at him, and told him not to move. Moore shot at Hadden, and Hadden fell to the floor and pretended to be dead. After several more shots were fired, Hadden heard the doorbell to the store ring. He heard Moore’s pickup truck and saw him drive off on Highway 221. Hadden got up and saw Mahoney lying face down, with a gun about two inches from his hand; he then called 911. Mahoney died within minutes from a gunshot wound through his heart. A money bag with $1408.00 was stolen from the store.

Shortly after the incident, Deputy Bobby Rollins patrolled the vicinity looking for the perpetrator of the crime. Approximately one and one-half miles from the convenience store, Deputy Rollins took a right onto Hillside drive, where he heard a loud bang, the sound of Moore’s truck backing into a telephone pole. He turned his lights and saw Moore sitting in the back of a pickup truck bleeding profusely from his left arm. As Deputy Rollins ordered him to the ground, Moore advised him, “I did it. I did it. I give up. I give up.” A blood covered money bag was recovered from the front seat of Moore’s pick-up truck. The murder weapon, a .45 caliber automatic pistol, was found on a nearby highway shortly before daylight.

Moore was tried for the crimes in October 2001. The jury convicted him of all counts. In a separate sentencing proceeding, the jury recommended a sentence of death.

According to the case, Moore spoke to the jury during the guilt phase of the trial.

“All I know is my life is in jeopardy here a second time,” he said. “The state is seeking the death penalty on me, which means my very life is at stake.”

The state objected. The guilt phase of the trial is about guilt, not about punishment — and Moore was speaking about punishment, not guilt. The judge sustained the objection, and the South Carolina Supreme Court held that the court did not err in its ruling.

READ RELATED: Odette Lysse Joassaint Murdered Two of Her Children: Police

During the actual penalty phase of the trial, Moore stayed silent. He then appealed by claiming he was dissuaded from making “a closing argument asking for mercy and/or expressing feelings of remorse.” Again, the South Carolina Supreme Court disagreed with his claim on appeal.

“The death sentence was not the result of passion, prejudice, or any other arbitrary factor, and the jury’s finding of aggravating circumstances is supported by the evidence,” the state high court held. “Further, the death penalty is not excessive or disproportionate to the penalty imposed in similar capital cases.”

Richard Bernard Moore appears in an earlier mugshot.

A subsequent habeas corpus case decided by the same high court denied relief to Moore. It added additional facts to the narrative of what occurred at the convenience store in 1999, and it identified the victim of the shooting by a different name — James Mahoney:

At Moore’s trial in 2001, a witness who was a frequent customer at Nikki’s Speedy Mart testified that he saw Moore enter the store and walk over to a cooler shortly after 3:00 a.m. The witness was seated at a gaming machine, playing video poker. A few moments later, he heard Mahoney exclaim, “What the hell do you think you are doing?” The witness swiveled his seat around and noticed Moore had a gun and was holding both of Mahoney’s hands with one hand. Moore told the witness not to move and immediately shot at him. The witness was not struck, but he dropped to the floor and played dead.

The witness then heard more gunshots before Moore fled the scene in a loud pickup truck, taking a moneybag from behind the counter. The witness discovered Moore had shot Mahoney in the chest, killing him. Mahoney had also suffered a wound to his arm, which could have been caused by the same gunshot. A meat cleaver of unknown origin was lying near the body.

Moore was shot in his left arm during the incident. There was no evidence that Moore entered the store with a gun. Rather, the forensic evidence established Moore killed Mahoney with a gun that belonged to the store’s owner. Witnesses testified that Mahoney usually carried a gun on his person for protection when he worked late at night, and the store’s owner kept several guns on the premises, under the counter.

The State asserted Moore’s motive was to obtain money to purchase crack cocaine. George Gibson testified Moore had tried to obtain crack cocaine from him earlier in the evening, but he turned Moore down because he had no money. After the shooting death of Mahoney, Moore went back to Gibson, informing him that he had money but had done something bad and needed to turn himself in. Moore sought drugs and assistance to get to the emergency room, as he was bleeding profusely from his left arm, but Gibson declined Moore’s requests. As Moore was backing out of Gibson’s yard to leave, he accidentally struck a telephone pole, which caught the attention of a passing officer.

When the officer approached, Moore got out of his truck and laid down in the road, stating, “I did it, I did it, I give up, I give up.” On the front seat of Moore’s truck, the officer saw a blue moneybag belonging to Nikki’s Speedy Mart that had blood on it, as well as a pile of loose money that was covered in blood. The total recovered was $1,408.00. A pocketknife was lying on the seat, under the money.

The habeas corpus case noted that Moore offered a different version of the story during a post-conviction review hearing in 2011:

He alleged Mahoney was the aggressor, that he took a gun away from Mahoney after a struggle and fired “blindly” at him after seeking cover, and that he took the bag of money only as an after-thought as he left the store. Moore further maintained that he went to Gibson’s home immediately after the shooting to get help for the injury to his arm, not to obtain drugs.

A footnote explained further:

Moore testified that he usually went to Nikki’s Speedy Mart two or three times a week, but had recently lost his job. Moore stated he was sure Mahoney recognized him from their prior interactions. For example, Mahoney had helped him purchase a lighter and filled it for him. Moore claimed that, on the night of Mahoney’s death, he was short of change and had asked Mahoney if he could use money from a “change cup” on the counter, but Mahoney said “no” and the two had words. Moore maintained Mahoney pulled out a gun when he refused to leave the store, and Mahoney was shot when they struggled over the gun.

The Supreme Court majority rubbished the defendant’s arguments that the death penalty was disproportionate to the facts of the case.

A sole justice, Kaye G. Hearn, issued a partial dissent.

“I write separately to express my view that our system is broken and to disagree with that part of the majority opinion which finds Petitioner Richard Moore’s sentence proportionate to his crime,” Justice Hearn wrote. “My disagreement with the majority has nothing to do with the reliability of Moore’s convictions. Unquestionably, Moore is guilty. But that is not the end of the inquiry; rather, it is only the beginning, as a death sentence demands the highest protections afforded by law due to its obvious severity and finality.”

Justice Hearn argued that because Moore was unarmed when he entered the convenience store, he shouldn’t be put to death; Hearn said there was a “vast difference between a ‘robbery gone bad’ and a planned and premeditated murder.” That is a distinction, she argued, that “numerous other states” — including Florida — have used to wipe way death sentences imposed by juries.

A criminal justice reform group recently criticized the Palmetto State’s decision to revive firing squads as a legal form of execution:

By adopting the firing squad, South Carolina has become an outlier, reverting to an execution method previously abandoned by most jurisdictions as barbaric. Indeed, only three people in the United States have been executed by firing squad since the return of the American death penalty in 1976, a tiny fraction of the more than 1,500 total executions in the same period. If executions proceed by firing squad, South Carolina will join China, Iran, North Korea as one of the few jurisdictions in the world carrying out executions by firing squad.

Moore is scheduled to die on April 29, according to a South Carolina Department of Corrections press release. His attorneys are continuing with efforts to block the execution.

Read the DOC press release and the aforementioned court papers below:

Have a tip we should know? [email protected]

Source: