It’s weird yet true that in the wake of Alito’s draft opinion overturning Roe being leaked to the press, neither Republicans nor Democrats seem to want to talk much about … abortion. Republicans have focused instead on criticism of the leak, probably because they know what the polling on Roe looks like. Democrats, meanwhile, have taken to warning that abortion is merely the first domino to fall. With the unwritten right of privacy now out the window, there’s no telling what other rights Americans take for granted will soon be on the judicial chopping block.

A few days ago Eric Swalwell wet his pants about how Republicans were supposedly coming for interracial marriage, never mind that the case in which that right was recognized has more to do with equal protection than with privacy. Now here’s Hillary Clinton making a similar point with less specificity. The parade of horribles is coming, she says:

EXCLUSIVE: Hillary Clinton’s first interview on the implications of this week’s Roe v. Wade news: “It is not just about a woman’s right to choose. It is about much more than that.”

Watch the interview TONIGHT on the @CBSEveningNews with @NorahODonnell. https://t.co/0eUrRo3eHq pic.twitter.com/xpenZF0aMB

— CBS News (@CBSNews) May 5, 2022

Is the parade of horribles coming?

Re-read this post for the key bits from Alito’s opinion. For an unwritten right to be fundamental and protected by the Constitution, he writes, it needs to be “deeply rooted” in the country’s history. Marriage, one would think, is an easy call; it’s deeply rooted. Abortion, or some general right of privacy writ large, is another matter. And if that’s true, what about a right to contraception? Or the right of gays to engage in consensual sex? Those are both based on the right of privacy as well. If the state can regulate abortion post-Roe, shouldn’t it be able to regulate those? Legal scholars are wondering:

“What we wind up seeing is to what extent is Griswold v. Connecticut [which found a right to contraception] the next one to fall,” he continued. “Roe v. Wade is problematic. I’ll call Roe versus Wade a punch to the gut. Griswold v. Connecticut, if it were to go next, that right to privacy as inferred would be a blow to the head.”

Geoffrey Stone, a professor of constitutional law at the University of Chicago, echoed the sentiment, saying “it’s perfectly plausible that [the Supreme Court] will say, ‘We already decided it. There’s no right of privacy in the Constitution.’”

“A key part of the rationale of Alito’s opinion is that there is no such thing as a right of privacy in the Constitution. That’s what the court relied upon in all of these cases,” Stone told Insider. “If that’s true in Dobbs, then why isn’t true in others?”

Alito’s draft emphasized that abortion is different because it involves life and death and therefore his opinion shouldn’t be read as calling any other rights into question. But that’s semantics. The logic of the opinion, that unwritten rights not deeply rooted in American history are unprotected by the Constitution means the rights to contraception, gay sex, and gay marriage are all prime for revisiting by the Court.

But are there five votes to do that?

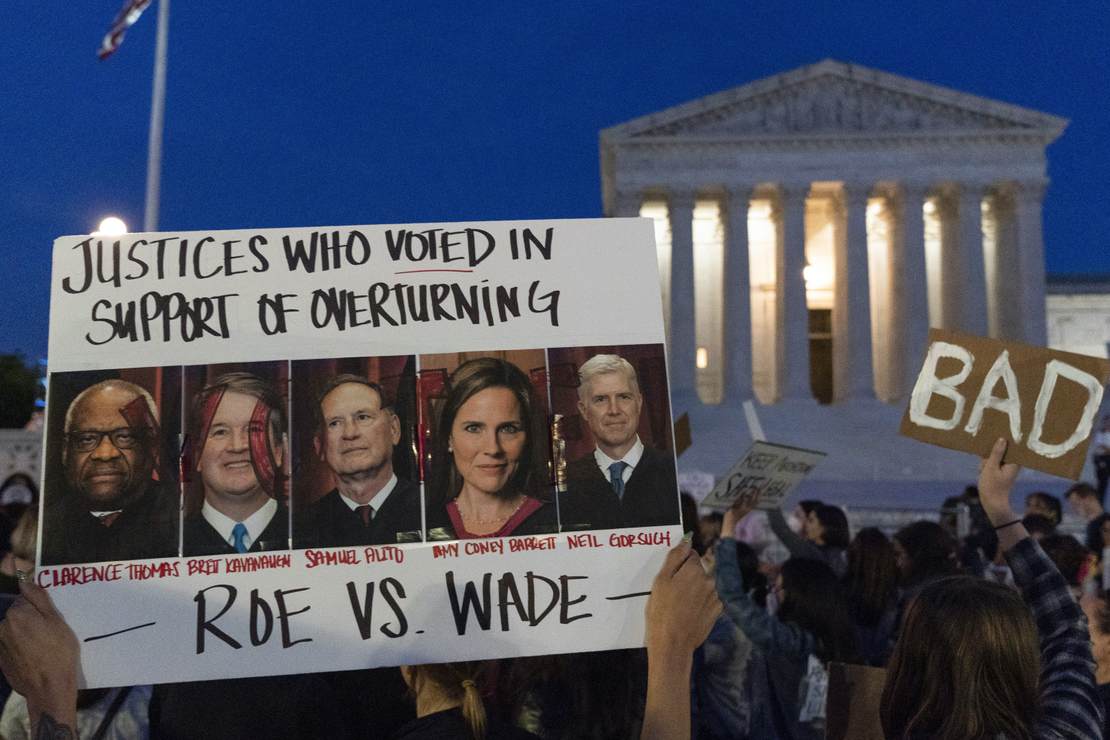

Alito would do it, no doubt. He dissented from the Obergefell decision legalizing gay marriage precisely because that practice wasn’t “deeply rooted” in American history. My sense in reading his Dobbs draft, though, was that he included the language making clear that the ruling applies only to abortion because one or more of the other justices in the majority was squeamish about undercutting the Court’s privacy jurisprudence writ large. Maybe Kavanaugh, Barrett, Gorsuch or some combination (probably not Thomas) thinks yanking the rug out from under gay marriage is a bridge too far. So Alito compromised to get their votes. Roe goes, but only Roe.

READ RELATED: Is the top Republican on the Senate intelligence Committee trying to tell us something about Putin?

Ramesh Ponnuru is also skeptical that the Court will take a hatchet to other precedents in the privacy realm. Don’t forget that SCOTUS can’t just take up issues on its own initiative, he notes. There has to be enough of a public appetite to revisit an issue that a state government will feel compelled to address it via legislation. That appetite has always existed with abortion. Does it exist for contraception, gay sex, or marriage?

The decades-long campaign of resistance to Roe also sets it apart from those rulings. Griswold and Lawrence didn’t lead to any such campaign. Without state legislation to outlaw contraception or sodomy, even a justice who wanted to overturn those rulings would not have any occasion to do it. (This is something Justice Amy Coney Barrett tried to explain during her confirmation hearings.)

Opponents of Roe also had the option to fight it in increments. They could ban some types of late-term abortions, require parental notification or restrict the activities of women’s health clinics, for example, and ask the courts to allow those laws. Eventually, they built up to bans on abortion after 15 weeks of gestational age, the restriction specified by the 2018 Mississippi law that has put the issue before the Supreme Court now. These laws are popular in most polls, gaining support even from some people who consider themselves pro-choice, but directly conflict with Roe. As both parties arguing the Mississippi case agreed, the justices had to choose between keeping the law and keeping Roe.

Same-sex marriage is, by contrast, a binary choice; there’s no equivalent strategy for chipping away at the right in legislatures and courts.

Public support for interracial marriage and legal access to contraception is practically unanimous. I don’t know what the polling on gay sex is, but the fact that a solid majority now supports gay marriage suggests there’d be plenty of support for not throwing gays into prison for sex acts as well. As such, a state legislature that wants to force SCOTUS to take up any of those issues would first have to reckon with the politics of passing a bill that’s apt to alienate many voters. And not just the electoral politics: I suspect we’d see major corporate and grassroots boycotts of any state that went in this direction.

All of which is a long way of making a point that some people seem surprisingly incapable of grasping amid the uproar this week over Alito’s opinion: Just because the Court says a state has power to regulate something doesn’t mean it’s politically feasible for that state to do so. In fact, on some of these issues — maybe even on abortion — I suspect nervous legislators will attempt to punt the matter to voters by asking them to hold a referendum and decide for themselves what the policy should be.

To the extent that none of this is enough to calm Democrats and other supporters of these rights, they can always try to use whatever legislative power they currently enjoy to codify them:

In other words: there are things states can do now to protect rights that might not survive a SCOTUS majority bent on paring back substantive due process.

There’s no need to wait until SCOTUS decides to make it an issue.

— Gabriel Malor (@gabrielmalor) May 5, 2022

Better safe than sorry. The spirit of the populist moment we’re in is culturally irredentist; the more ground it gains, the more the momentum of the advance may carry it towards strongholds the left thought were safe. I’ll leave you with Ben Shapiro, who suspects that gay marriage is here to stay but is willing to see it undone if SCOTUS is.

Ben Shapiro: “Obergefell is a bad Supreme Court decision and if we had a Supreme Court worth its salt, they would overturn Obergefell” pic.twitter.com/APcKjramGU

— Jason Campbell (@JasonSCampbell) May 4, 2022

Source: