The season of coughs is upon us. As the weather gets colder, we spend more time indoors, which leads to viruses passing more easily from person to person.

But while most coughs are due to mild viral infections and clear up on their own, many people suffer from coughs that last for weeks, months or even years – officially a cough that lasts beyond eight weeks is defined as chronic.

‘It’s important to stress that, for most people, the cause of a chronic cough is usually benign,’ says Dr Sean Parker, a consultant respiratory physician and co-chair of the recent British Thoracic Society cough guidelines.

‘However, there are certain symptoms that, when accompanying a cough, can be significant and need further investigation to rule out any thing sinister.’

Coughing is essentially a good thing – it’s an important reflex action, explains Dr Edward Nash, a consultant respiratory physician at George Eliot Hospital in Nuneaton.

Between 3 and 18 per cent of adult suffer from a chronic cough

‘It happens when something irritates the airways, stimulating nerves that send a message through to your brain.

‘This, in turn, tells the muscles in your chest and abdomen to push air out of your lungs and force out the irritant.

‘In essence, it helps get rid of stuff that doesn’t belong there – such as mucus, inhaled dirt or food – and at quite a speed too. It can propel air and particles out at speeds close to 50mph,’ adds Dr Nash.

But with a chronic cough, which affects 3 to 18 per cent of adults, there may be an underlying cause to this irritation ‘and in these cases it may require medical attention’, he says.

So when should you seek medical help? And what’s the best way to ease your symptoms? In this essential guide to common ailments, a panel of leading experts provides the answers, based on the latest scientific evidence.

SO WHAT’S CAUSING IT?

There’s a range of different coughs out there – and recognising the type you have can sometimes point to a possible cause.

A wet cough, also known as a ‘productive’ cough, brings up fluid or phlegm. Several respiratory infections – such as flu or pneumonia – can cause this.

More serious causes include chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and heart failure, where fluid can leak into the air sacs within the lungs.

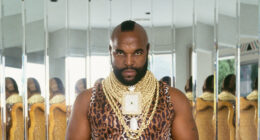

Dr Edward Nash, a consultant respiratory physician, says coughing can propel air and particles out at speeds close to 50mph

When no mucus or phlegm is brought up, it’s known as a dry, or ‘non-productive’ cough. It can be accompanied by a tickly, irritating feeling in the throat.

Covid is a well-known cause. A dry cough is also a symptom of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (GORD), where stomach acid leaks up the oesophagus.

Chronic refractory cough, where the nerves controlling the cough reflex are particularly sensitive is another cause – as is lung cancer, although this is generally accompanied by other symptoms, including unplanned weight loss.

It is important to note that all coughs can change and there are situations that don’t produce the ‘typical’ cough for that condition, advises Dr Paul Marsden, a consultant in respiratory medicine at Wythenshawe Hospital in Manchester. This is why you need to be aware of any other symptoms you may have alongside the cough.

Here, Dr Parker and Dr Marsden examine some of the most common types of persistent cough – and their potential causes. Note, you should always consult a doctor if your cough has lasted three weeks.

WET COUGH

This is the kind of cough we associate with viral infections such as colds and flu, bringing up fluid or phlegm. The fluid or phlegm irritates the airways, triggering the cough reflex.

It may also feel like there’s something rattling or crackling in your chest when you breathe and it’s usually accompanied by a multitude of other symptoms such as a runny nose and general tiredness.

‘These are generally self-limiting, meaning you can deal with them at home and things should improve within three to four weeks,’ says Dr Marsden.

A wet cough can also be caused by bacterial infections such as pneumonia (a serious lung infection that requires urgent treatment) and whooping cough – although the wet cough in the latter is distinctive, leading to uncontrollable coughing fits.

CHESTY, WET COUGH

A chronic chesty cough that won’t go away can be one of the first signs of COPD, the umbrella term for progressive lung diseases such as chronic bronchitis and emphysema that lead to blocked airflow from the lungs.

Most people with COPD are smokers or former smokers and other symptoms can include shortness of breath and persistent chest infections.

This is diagnosed with tests that show how well your lungs are working – a spirometry test, for instance, which measures how much air you can breathe in and out. You may require X-rays.

Treatment includes inhalers to open the airways, inhaled steroids and mucolytic drugs (that break up mucus in the lungs, making it easier to cough out).

‘As well as giving up smoking, maintaining physical activity and fitness is vital, so rehabilitation classes with physiotherapy can really help some patients,’ adds Dr Parker.

VERY DRY, NON-PRODUCTIVE COUGH

As well as Covid, another common cause of this type of cough is asthma, triggered by inflammation of the airways – although cough is a less common symptom than the characteristic wheezing and shortness of breath.

Asthma causes the airways to constrict, making it harder to breathe – and it’s this irritation that can also cause coughing.

‘When cough is the only symptom, it can be much harder to diagnose,’ says Dr Parker.

‘The doctor would examine you and conduct tests, such as a spirometry test. They may also measure how much nitric oxide you exhale; high levels can be a sign of an inflamed airway.

‘The best treatment is prescribed steroid inhalers to reduce swelling and inflammation.’

DRY COUGH THAT TURNS PHLEGMY

Smoking is one of the most common causes of chronic cough. It’s caused by the body trying to clear the tobacco chemicals from the airways and lungs: the phlegm is the result of the smoke irritating the airways.

If you quit smoking, your cough should improve within a few months (although it may worsen initially as your body clears out all the mucus in your lungs).

FREQUENT, DRY HACKING COUGH

A dry, hacking cough can be a side-effect of drugs prescribed for high blood pressure and heart failure – ACE inhibitors, which include perindopril and ramipril (ramipril is the fifth most prescribed medication in the UK).

This side-effect occurs in up to 10 per cent of people and is more common in women – possibly because of ‘an innate difference in the cough reflex’, says Dr Parker.

It’s thought ACE inhibitors cause the build-up of bradykinin in the airways. This compound plays a role in the body’s inflammatory response and this build-up may make nerves in the airway overly sensitive. If the cough is affecting day-to-day life, it’s possible to swap to a different class of drug, known as ARBs (angiotensin receptor blocker, such as losartan), which is not associated with cough.

BARKING COUGH THAT SOUNDS LIKE A SEAL

Easy to recognise, the barking cough, like the noise made by a seal, is a symptom of croup which mainly affects babies and young children. Commonly caused by a virus, an infection of the upper airway leads to swelling around the voice box (larynx), windpipe (trachea) and bronchial tubes. This narrows the upper airways, making it harder to breathe.

‘The barking sound is produced as air forces its way through the narrowed passage past the swollen vocal cords,’ says Dr Parker.

‘Croup is rare in adults because children have smaller airways so are more affected.’ (This should improve within 48 hours, but if it doesn’t then take your child to see a doctor.)

COUGHING FITS THAT AFFECT BREATHING

Coughing so hard you struggle to breathe is known as paroxysmal coughing. It can occasionally be so intense that people vomit. It’s associated with many conditions including asthma, pneumonia and whooping cough – or pertussis, also known as the 100-day cough.

Pertussis is a highly contagious bacterial lung infection; the cough occurs after roughly two weeks. Because you’re coughing for so long, it can be hard to catch your breath and you end up breathing in suddenly, with some of those affected making ‘whooping’ sounds between coughs.

Treatment is usually with antibiotics. However, babies under six months old or those with severe whooping cough, may require hospital treatment.

PERSISTENT, DRY TICKLY COUGH

A dry, tickling cough that remains after eight weeks and has not responded to medication could be what’s known as refractory chronic cough, a common complaint estimated to affect up to one in ten people, more of them women, although it’s not understood why.

This cough can be triggered by anything from talking through to strong smells, even temperature change.

Some people can cough almost constantly, while it can affect others in bursts. In extreme cases, patients experience blackouts as they struggle to breathe. The condition can afflict some for decades.

‘Diagnosis can only occur when all other causes of chronic cough such as asthma, have been dismissed or controlled and the cough remains despite medical treatment,’ says Dr Marsden.

‘Some patients have it for years and, understandably, it has a major impact on their life, affecting sleep, social life – everything. This can lead to depression and knock-on effects such as incontinence, chest pain and hernia.’

Emerging research suggests that it is caused by a sensitivity of the nerves controlling the cough reflex.

Treatment can involve referral to speech and language therapists to learn breathing exercises to manage your cough and control the tickle.

Medication can also help. A new treatment option is daily morphine sulphate tablets (5g – the lowest available dose).

While it isn’t fully understood how this works, it’s thought it affects the central nervous system (in the brain).

You need to be prescribed it by a specialist and be closely monitored as it can be addictive.

Other drugs such as gabapentin and pregabalin, which are used to treat nerve pain, may also reduce symptoms but can have side-effects including drowsiness, constipation and dependency. A new tablet, gefapixant, was licensed in the UK to treat refractory cough last year – currently it’s only available on private prescription.

‘The drug blocks a receptor on the vagus nerve, which is one of the main nerves involved in triggering cough and trials showed it reduced cough frequency by 18.5 per cent after three months compared with a placebo,’ explains Dr Marsden, who leads the Manchester Chronic Cough Service.

‘However, it can have side-effects, such as a change in taste.

‘Another version, camlipixant, is in late-stage clinical trials. With an estimated 40 per cent of people attending chronic cough clinics suffering from refractory cough, it’s likely many will benefit from these medications.’

DRY COUGH THAT’S WORSE AT NIGHT

This could be a sign of acid reflux, where a leaky valve at the bottom of the oesophagus (or gullet) allows the stomach contents to leak back up.

While the main symptom is heartburn, it can also trigger a dry cough with no other symptoms (known as ‘silent’ reflux), as the stomach acid irritates the gullet.

The cough generally only happens at night, after you’ve had a meal, when you lie down or sometimes when you wake up in the morning.

GORD can be diagnosed by your GP based on your symptoms, although you may be referred for an endoscopy – this is where a tiny camera on the end of a long tube is inserted, via the throat, to check the inside of the oesophagus and stomach.

Treatment for GORD generally involves proton pump inhibitors (PPIs), drugs that reduce stomach acid production.

If there are still symptoms, anti-reflux surgery – known as a Nissen fundoplication – could be an option: this tightens the valve between the oesophagus and stomach. But if the cough doesn’t improve, other causes may then need to be considered, such as refractory chronic cough, says Dr Marsden.

COUGH WITH URGE TO CLEAR THROAT

A cough with the feeling that something is in the back of your throat can be related to rhinosinusitis, a common problem where the nose and the sinuses (the air-filled spaces behind the forehead, nose and cheeks) can become inflamed, usually following colds, flu or allergies.

The cough can be accompanied by a blocked or runny nose, facial pressure near the cheeks and headaches.

The cough is often thought to be due to excess mucus running down the back of the throat (known as post-nasal drip).

However, the latest research suggests there may not in fact be a significant increase in mucus.

‘For many people the cough is now thought to be the result of a change in the direct connection between the sensory nerves in the upper airways and the brain’s control centre for coughing,’ says Dr Parker.

‘In essence, the rhinosinusitis irritates sensory nerves, which make the cough reflex hypersensitive.’

Treatment involves over-the-counter antihistamines – or pharmacy-only ones containing decongestants – to dry out the mucus.

Nasal spray decongestants can also help, but make sure you use those containing oxymetazoline sparingly – no more than for a couple of days – as long-term use can cause a ‘rebound’ effect, making the congestion worse.

While medication can help, in many cases the cough remains and the diagnosis may be refractory chronic cough.

Hayfever, or allergic rhinitis, which affects up to 25 per cent of adults in the UK, can cause similar cough symptoms.

YOUR COUGH COLOUR CODE

Watch out for changes to the colour of your phlegm, says Dr Edward Nash, as it can be a sign of a ‘potential health concern’

Coughing up phlegm is usually nothing to worry about, says consultant respiratory physician Dr Edward Nash.

‘Phlegm is produced by the thin membranes that line your upper and lower airways and it helps to rid the airways of any irritants.

‘It does this with help from small hair-like structures [cilia] that essentially bring the mucus up to the back of the throat, where it can be swallowed or coughed out as phlegm.

‘Sometimes, however, for instance when there’s more of it than usual, it changes colour or it’s a different consistency. This can be a sign of a potential health concern.’

Frothy

Persistent production of clear frothy sputum can suggest a build-up of fluid in the lungs (pulmonary oedema) caused by heart disease and is a sign that the heart is not pumping properly (known as heart failure). ‘If this is associated with difficulty in breathing and ankle swelling, it is particularly important to seek medical attention,’ says Dr Nash.

Red/pink tinge

‘Any suggestion of blood in your phlegm and you need to seek medical attention,’ says Dr Nash. Coughing up blood can be a symptom of pneumonia, a blood clot on the lung (pulmonary embolus) or other serious conditions that must be dealt with immediately.

White/clear

This is the normal colour of phlegm. It is mostly made up of water, with some added proteins, antibodies and dissolved salts. If you start coughing up more phlegm than usual, it can suggest a viral infection or an allergy.

Brown

People who smoke often have brown phlegm, which is caused by inhaling chemicals (such as tar) contained in tobacco. Breathing in air pollution and certain dusts (such as coal dust) can also cause the discolouration. Stopping smoking allows the cilia to work more effectively, although you may cough up more phlegm than usual for the first few weeks or months after you have quit. The colour of your phlegm should eventually return to a more normal white/clear hue.

Dark yellow/green

This suggests a chest infection, more likely caused by bacteria. ‘The darker colour is caused by chemicals released by white blood cells in an attempt to fight the bacteria,’ says Dr Nash. ‘If you feel unwell and this lasts more than five days, seek medical attention as you may need antibiotics.’ If your phlegm is persistently thick and sticky, see your GP – you may need medication to loosen it and possibly a referral to a specialist.

HOW BREATHING EXERCISES HELP

Try different breathing exercises to keep pesky coughs at bay

‘Whether your cough is wet or dry, there are breathing techniques which, alongside any medication, can help both manage and reduce the urge to cough,’ says Jennifer Butler, a speech and language therapist at Northumbria Healthcare NHS Foundation Trust.

Here, she gives some exercises that might help.

Wet cough: If your cough is full of phlegm, breathing in deeply and holding it allows air to get behind the mucus so it can be coughed out.

1. Take a slow, deep breath in through your nose and hold for a few seconds before letting it out through the mouth. Repeat four times.

2. Try gentle, relaxed breathing for 30 seconds.

3. Repeat steps one and two, three times.

4. Huff three times (take a slow, deep breath in through your nose, then breathe out quickly, as if you were steaming up a mirror).

5. Repeat three times.

Dry or tickly coughs: ‘A dry cough often starts with a tickle in the throat, leading to a cough,’ says Jennifer Butler.

‘Unfortunately, one cough tends to lead to another as you fuel the irritation by taking another deep breath; the action of coughing can also further irritate the throat.’

This technique may help to reduce the frequency:

1. The minute you feel you’re about to cough, take a sip of water or swallow saliva.

2. If the tickle remains, breathe in through your nose, or pursed lips, for one second, this filters the air more effectively than through an open mouth.

3. Breathe out through pursed lips for three seconds. And tell yourself that if there’s nothing in your windpipe to eject, the cough won’t be helpful.

4. Repeat if you still feel a tickle.

WHY THE BEST REMEDIES ARE IN YOUR CUPBOARD

‘Honey has antioxidant properties which may soothe the throat by relieving inflammation,’ says GP Dr Mark Peters

There are three main types of cough medication.

Suppressants are targeted at dry, tickly coughs. The active ingredient, dextromethorphan, reduces activity in the part of the brain that causes coughing, says Laura Wilson, director of the Royal Pharmaceutical Society in Scotland.

Products include Robitussin Dry Cough and Covonia Bronchial Balsam Syrup.

Meanwhile, expectorants ‘loosen’ mucus by increasing its water content in the lungs, so it’s easier to cough out.

The active ingredient is guaifenesin, found in products such as Lemsip Cough and Benylin Mucus Cough Max.

Finally, there are combination medicines, which incorporate the effect of a suppressant or expectorant with another ingredient such as decongestants (which clear congested airways) for a bunged-up nose – and painkillers, for cold-related headaches. Examples include Night Nurse Capsules.

But are they effective?

No, suggests Dr Paul Marsden, a consultant in respiratory medicine at Wythenshawe Hospital in Manchester.

‘There is no robust evidence that any over-the-counter medicines reduce cough,’ he says.

Indeed, in 2014, a review by the highly respected Cochrane group found there was ‘no good evidence for or against’ the use of over-the-counter cough medicines sold in the UK.

What about the abundance of old-fashioned or natural remedies for easing coughs? Even the NHS website has some suggestions, but do any of them help?

Here Dr Mark Peters, a GP based in South-West London, looks at some of the most popular.

HONEY: There’s quite a bit of evidence to suggest that honey can help to soothe coughs, says Dr Peters.

This includes a Cochrane review that assessed the data of previous trials, involving 265 children aged two to five comparing the use of honey against a common cough suppressant or an antihistamine.

It found that honey was better than no treatment, slightly better than the antihistamine and as effective as the suppressant in reducing the frequency of coughing.

‘Honey has antioxidant properties which may soothe the throat by relieving inflammation,’ says Dr Peters.

As for honey and lemon, while there’s little evidence for the benefit of lemon, the heat from the hot water used to make the drink may help to open up the airways, he says, adding: ‘It’s worth a try and a lot cheaper than over-the-counter medicines that often contain honey.’

PELARGONIUM: This herbal remedy, derived from a type of geranium, is listed as a cough treatment on the NHS website. Several studies suggest it can be effective, including a 2022 trial in the journal Multidisciplinary Respiratory Medicine involving 2,195 participants with acute cough.

The researchers found that seven days’ treatment with pelargonium extract both reduced cough intensity and the amount of coughing itself.

‘Exactly how it works is unknown, however it’s thought to have antibacterial and antiviral effects,’ says Dr Peters.

SALT: Gargling a simple solution of salt and water can help ease coughing.

A 2019 trial by the University of Edinburgh found that participants (who’d contracted a cold within the previous two days) who gargled and cleared their nose with a saltwater solution reported fewer coughs and less congestion.

Gargling also cut the length of their cold by almost two days.

The researchers said the salt may work by boosting cells’ antiviral defence.

‘Whilst evidence of guaranteed results is limited, saline is a safe, accessible and affordable remedy,’ says Dr Peters.

To make the solution, simply mix half a teaspoon of salt in a glass of warm water and stir until it dissolves.