Amy Coney Barrett was photographed on Capitol Hill on October 21, 2020.

In a 182-page series of opinions, the Iowa Supreme Court on Friday overruled an abortion rights decision that was only four years old. By so doing, the court ruled that the Iowa Constitution does not contain a “fundamental right” to an abortion and that legislative statutes which seek to regulate abortions will be judged under a more lenient standard of judicial review.

A brief look at abortion litigation in Iowa is necessary to understand Friday’s opinion. In 2018, the Court held that the Due Process Clause of the Iowa Constitution “protected abortion as a fundamental right.” Accordingly, the Court ruled in 2018, a state statute which required a 72-hour waiting period “could not survive strict scrutiny” and was therefore unconstitutional.

That preschool-age decision, by a majority that was then 5 to 2, now stands in the trash heap of Hawkeye State litigation. The court held on Friday that the 2018 decision “can and should be overruled” — in part because of its infancy.

The makeup of the Iowa Supreme Court has changed significantly over the last four years. Gov. Kim Reynolds, a Republican, has appointed four of the Court’s seven sitting justices since the 2018 decision was penned.

“Coincidentally, all four outgoing justices were part of the 5–2 majority that recognized a fundamental right to decide whether to continue or terminate a pregnancy in the 2018 case, which the State asks us to overrule just four years later,” Chief Justice Susan Christensen noted in a partial concurrence and partial dissent.

A YouTube screengrab shows the beginning of the Iowa Supreme Court’s oral arguments Planned Parenthood of the Heartland v. Reynolds on Feb. 24, 2022.

Justice Edward Mansfield explained the court’s new abortion holding as follows:

Although we overrule PPH II [the 2018 decision], and thus reject the proposition that there is a fundamental right to an abortion in Iowa’s Constitution subjecting abortion regulation to strict scrutiny, we do not at this time decide what constitutional standard should replace it. As noted, in PPH I [an even earlier 2015 case], we applied the undue burden test under our constitution when the State conceded that it applied. An amicus curiae argues that we should hold that the rational basis test applies to abortion regulations. But the State takes no such position; it simply asks that PPH II be overruled and stops there. Moreover, the State did not seek summary judgment below (except as to the single-subject rule); it argued only that Planned Parenthood should not prevail as a matter of law based on issue preclusion.

In essence, since the court now believes that because there is no “fundamental right” to an abortion under the state constitution, the harsh “strict scrutiny” test no longer applies to laws which regulate the procedure.

Statutes which face a strict scrutiny analysis almost always are declared unconstitutional, so the court’s rubbishing of that test means that abortion regulations passed and promulgated by the state legislature have a better chance of standing without being struck down by a judge.

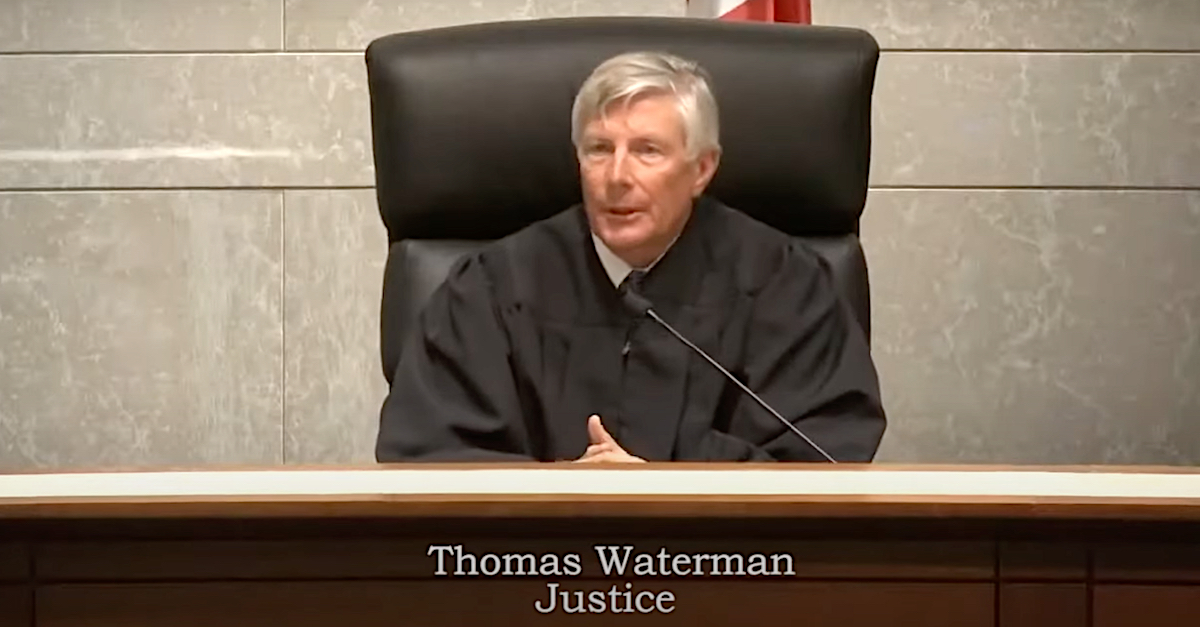

During oral arguments, Justice Thomas Waterman cited a Utah study which determined that 8% of women changed their minds about abortions because of statutory waiting periods. He asked “how many additional babies would be born in Iowa each year” if similar waiting periods were in effect in his state. (Image via YouTube screengrab.)

The proverbial elephant in the room, of course, is a looming U.S. Supreme Court decision concerning whether the federal constitution will continue to be interpreted to provide a right to abortion nationwide. A leaked draft opinion penned by Justice Samuel Alito suggests that the U.S. Supreme Court is ready to wipe clean that right. The Iowa Supreme Court addressed that issue as follows:

In addition, we are not blind to the fact that an important abortion case is now pending in the United States Supreme Court. See Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Org., 141 S. Ct. 2619 (2021) (Mem.) (granting certiorari). That case could alter the federal constitutional landscape established by Roe and Casey. While we zealously guard our ability to interpret the Iowa Constitution independently of the Supreme Court’s interpretations of the Federal Constitution, the opinion (or opinions) in that case may provide insights that we are currently lacking.

Hence, all we hold today is that the Iowa Constitution is not the source of a fundamental right to an abortion necessitating a strict scrutiny standard of review for regulations affecting that right. For now, this means that the Casey undue burden test we applied in PPH I remains the governing standard. On remand, the parties should marshal and present evidence under that test, although the legal standard may also be litigated further.

The Iowa opinion was a complicated mix of a six-justice majority as to some of its parts, a five-justice majority as to several of its other parts, a two-justice dissent as to one section of the opinion, and two-justice dissent elsewhere. USA Today explained the jockeying positions of the jurists as follows:

READ RELATED: Judge Agrees to Delay Proud Boys Trial Until December 2022

Two justices wanted abortion to remain a constitutional right in Iowa, while two others wanted to remove nearly all legal impediments to abortion legislation.

Only two justices, Dana Oxley and Thomas Waterman, joined Mansfield for the full majority opinion. Chief Justice Susan Christensen and justices Christopher McDonald and Matthew McDermott joined Mansfield’s opinion in parts. Justice Brent Appel, the sole Democratic appointee on the court, wrote a dissenting opinion, and McDermott and Christensen both filed partial dissents.

The issue of stare decisis — whether to let the previous 2018 decision stand — was naturally part of the analysis. Here, the core Mansfield opinion cited the writings of then-law professor Amy Coney Barrett to say that the previous precedent really wasn’t that critical and, therefore, not worth following. The court included the following block quote from Justice Barrett’s frequently discussed 2015 Texas Law Review article about precedent as support for its abrupt institutional about-face:

To be sure, partisan politics are not a good reason for overturning precedent. But neither are they a good reason for deciding a case of first impression. One who believes that an overruling reflects votes cast based on political preference must believe that all cases (or at least all the hot-button ones) are decided that way, for there would be no reason for politics to taint reversals but not initial decisions. If all such decisions are based on politics, there is no reason why the precedent — itself thus tainted — is worthy of deference. (Nor, for that matter, would there be reason to accept the legitimacy of judicial review.) Basic confidence in the Supreme Court requires the assumption that, as a general matter, justices decide cases based on their honestly held beliefs about how the Constitution should be interpreted. If one is willing to make that assumption about the decision of cases of first impression, one should also be willing to make it about the decision to overrule precedent.

“In conclusion,” the Iowa Supreme Court wrote in an immediate refrain to those points, “we think any stare decisis considerations are relatively weak here because PPH II was a constitutional decision, it was decided only four years ago, it has not been reaffirmed, and it was consciously based on the notion that constitutional interpretation is subject to change.”

In dissent, Justice Brent R. Appel quoted the U.S. Supreme Court’s 1992 opinion in Planned Parenthood v. Casey:

“Liberty finds no refuge in a jurisprudence of doubt.” Yet, by rejecting the holdings in a 5–2 majority decision in Planned Parenthood of the Heartland v. Reynolds ex rel. State (Planned Parenthood II) decided only a few years ago in a nearly identical issue, and punting the case back to the district court, the court creates a jurisprudence of doubt about a liberty interest of the highest possible importance to every Iowa woman of reproductive age.

This jurisprudence of doubt is troublesome for three reasons. First, in recent years, approximately one in four women of reproductive age have exercised reproductive autonomy by choosing an abortion. This jurisprudence of doubt will plainly impact many women and the men who support them. Second, the weight and depth of a woman’s interest in reproductive autonomy involved in this case is so profound.

[ . . . ]

Third, this jurisprudence of doubt is entirely avoidable. The decision in Planned Parenthood II was dispositive when it was issued and should be dispositive today.

Appel’s scathing and voluminous dissent also contained a historical review: the “foremost advocates of criminalization of abortion were virulently sexist and racist,” he wrote.

The leading advocate of criminalization, Dr. Horatio Storer and his colleagues, vigorously resisted the entry of women into the medical profession. They defined abortion as “a female crime,” a breach of marital duty, and accused those women who sought abortion as lazy, against the maternal instinct, and “avoid[ing] the labor of caring for and rearing children.” Storer also believed abortion risked letting white people be outnumbered by immigrants. I decline to embrace a tradition with obvious sexist and racial motivation into our modern jurisprudence of reproductive autonomy.

A footnote in the 67-page main opinion put the issue in broader terms.

“[T]oday’s dissent does not even acknowledge that the State has a compelling interest in promoting human life,” that footnote reads. “To the contrary, [Appel’s] dissent says, ‘The State does not have a legitimate interest in protecting potential life before viability.’”

The full opinion (and all of the concurrences and dissents) are below:

Have a tip we should know? [email protected]

Source: