A note before we start: May is Mental Health Awareness Month. If you or someone you know is having suicidal thoughts, the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline is available 24 hours a day at 1-800-273-8255.

————————

Before I get started on today’s column, a bit of personal background I’ve shared before.

I woke up on September 11, 2001, only to find out I’d lost my grandmother. She was not in New York, the Pentagon, or any of the hijacked flights. She was in her home, alone, with her thoughts and a gun.

Until then, I was aware of what suicide and depression were, but I had never really experienced such topics until then. I was in eighth grade, and my world was drastically changed at that point.

When someone in your life chooses to take such a drastic step, you expect the overwhelming sadness that comes with it. What people don’t tell you about suicide is that you’ll also feel a wave of tremendous anger at the selfishness of the person. How dare they do this to you? Couldn’t they realize what they were inflicting on their friends and family?

How could they leave you behind like that?

Eventually, I was able to forgive. You come to realize that they felt they had no control and that was the one bit of control they felt they had left and they needed to take that opportunity. Depression is a mental illness. It doesn’t lead to rational choices. It is, at times, an unbearable emotional agony. They just want it to stop.

Later in life, I recognized the signs of depression in myself. For me, they are particularly manifest on the weekends. Between my family, my job in education, a daily radio show, and writing here, I am just too busy to stop and think about anything. But on the weekends, things slow down, and there is the chance that those negative thoughts creep in and just linger, dragging me down with them.

Thankfully, I’ve never had suicidal thoughts or any tendencies toward self-harm. I can thank my grandmother for that. I don’t ever want my family to experience that loss.

In the United States, though, the numbers are on the rise, and we’re not seeing it isolated to any one group in particular.

In college athletics, there’s a string of high-profile female athlete suicides. At Stanford, you have soccer athlete Katie Meyer. In Wisconsin, there’s track star, Sarah Shulze. At James Madison University, you have softball player Lauren Burnett.

In the military, sailors on the USS George Washington were moved off the aircraft carrier after a string of suicides among the crew over the last year.

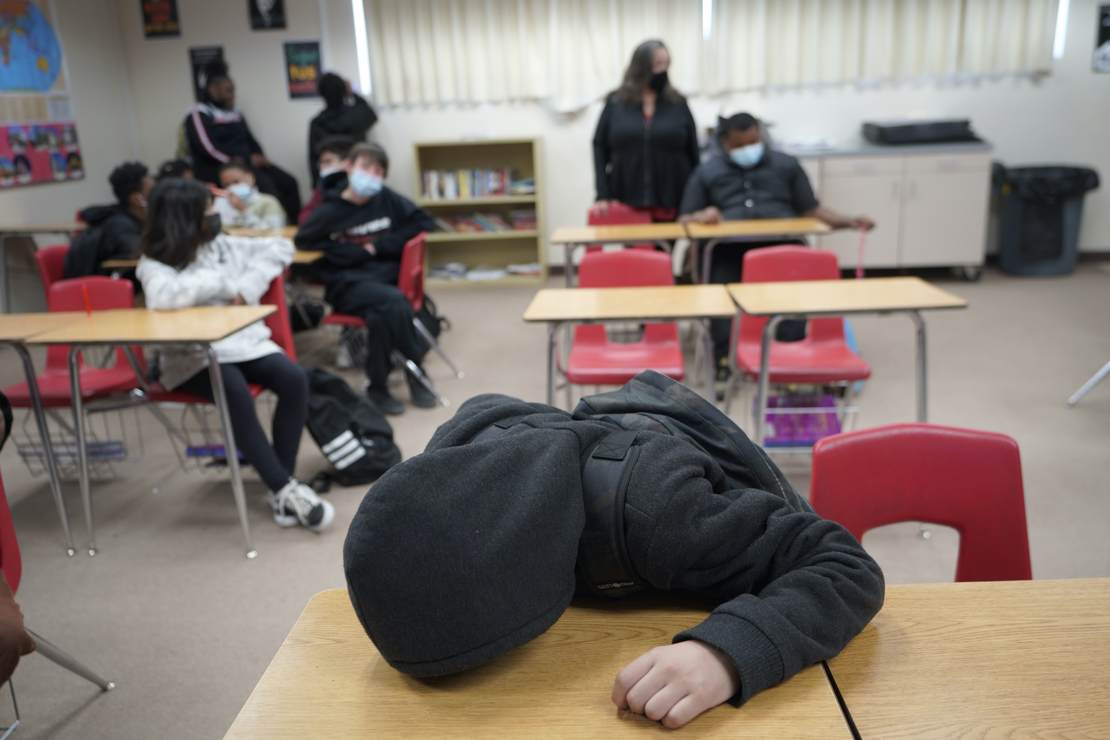

In the world of education, we’re definitely seeing teen depression, self-harm, and suicide is on the rise. Hospitalizations for mental health issues are becoming more frequent. There is a very noticeable, very tragic trend developing.

There’s a piece in The Atlantic recently that breaks down a lot of what we’re seeing among teens.

READ RELATED: Here's Why Biden's Putin-Regime Change 'Gaffe' Was So Egregious

The government survey of almost 8,000 high-school students, which was conducted in the first six months of 2021, found a great deal of variation in mental health among different groups. More than one in four girls reported that they had seriously contemplated attempting suicide during the pandemic, which was twice the rate of boys. Nearly half of LGBTQ teens said they had contemplated suicide during the pandemic, compared with 14 percent of their heterosexual peers. Sadness among white teens seems to be rising faster than among other groups.

But the big picture is the same across all categories: Almost every measure of mental health is getting worse, for every teenage demographic, and it’s happening all across the country. Since 2009, sadness and hopelessness have increased for every race; for straight teens and gay teens; for teens who say they’ve never had sex and for those who say they’ve had sex with males and/or females; for students in each year of high school; and for teens in all 50 states and the District of Columbia.

Currently, we blame a lot of this on the pandemic. Our kids were at home, isolated, and being deprived of intellectual, social, and emotional development for over a year. In some places, kids got back to school earlier than others, but for many the results were the same. Isolation was worse on students than the pandemic ever was.

But the pandemic is a recent catalyst that just made an already growing problem worse. The origins of our mental health crisis may actually be in 2012, when (as The Atlantic‘s writer points out) we first saw 50 percent or more of Americans owning a smartphone and social media began its explosive rise to dominance.

Social media isn’t like rat poison, which is toxic to almost everyone. It’s more like alcohol: a mildly addictive substance that can enhance social situations but can also lead to dependency and depression among a minority of users.

This is very close to the conclusion reached by none other than Instagram. The company’s internal research from 2020 found that, while most users had a positive relationship with the app, one-third of teen girls said “Instagram made them feel worse,” even though these girls “feel unable to stop themselves” from logging on. And if you don’t believe a company owned by Facebook, believe a big new study from Cambridge University, in which researchers looked at 84,000 people of all ages and found that social media was strongly associated with worse mental health during certain sensitive life periods, including for girls ages 11 to 13.

Why would social media affect teenage mental health in this way? One explanation is that teenagers (and teenage girls in particular) are uniquely sensitive to the judgment of friends, teachers, and the digital crowd. As I’ve written, social media seems to hijack this keen peer sensitivity and drive obsessive thinking about body image and popularity. The problem isn’t just that social media fuels anxiety but also that—as we’ll see—it makes it harder for today’s young people to cope with the pressures of growing up.

Social media is telling our girls how they are supposed to look and act. Armchair psychologists are telling our kids “You don’t fit in a predefined box. You’re different. You’re not male/female. You’re special. The world is out to get you because of it.” Kids are identifying as trans, gender fluid, etc. at insanely higher rates than ever before, and a lot of it is because they spent a year at home watching TikTok instead of being able to go out and hang out with friends.

But it’s not just teens. As adults, we are most isolated from each other than ever before. We are more connected than ever when it comes to our phones, but when it comes to in-person interaction, we’d rather sit in silence at the dinner table, texting each other, than actually talking.

We have forgotten the most important lesson of society: to come together and break bread with our neighbors. The political divide has played a major role in this — we are constantly looking at those who think differently than us and pushing them away rather than coming together. Both sides do it (though, yes, there are studies that routinely show progressives are less likely to have conservative friends than vice versa), and the result is that we fracture more and more as time goes on.

Humans are instinctively social creatures. We seek social interaction. That’s how we grow, develop, and even (god forbid) come up with new ideas or change our minds. But we’ve given up in-person interaction, which requires more emotional connection and empathy, for the cold, lifeless interactions through digital screens.

Our mental health crisis is at a tipping point. We need to heal, but we’re actively rejecting healing in favor of more division.

————————

As an aside, I spent two segments on my radio show covering this topic. Today’s column is based on those segments. You can listen to yesterday’s show on your preferred podcast platform (Apple, Spotify, Stitcher, or Amazon) or check out the abridged version below.

Source: