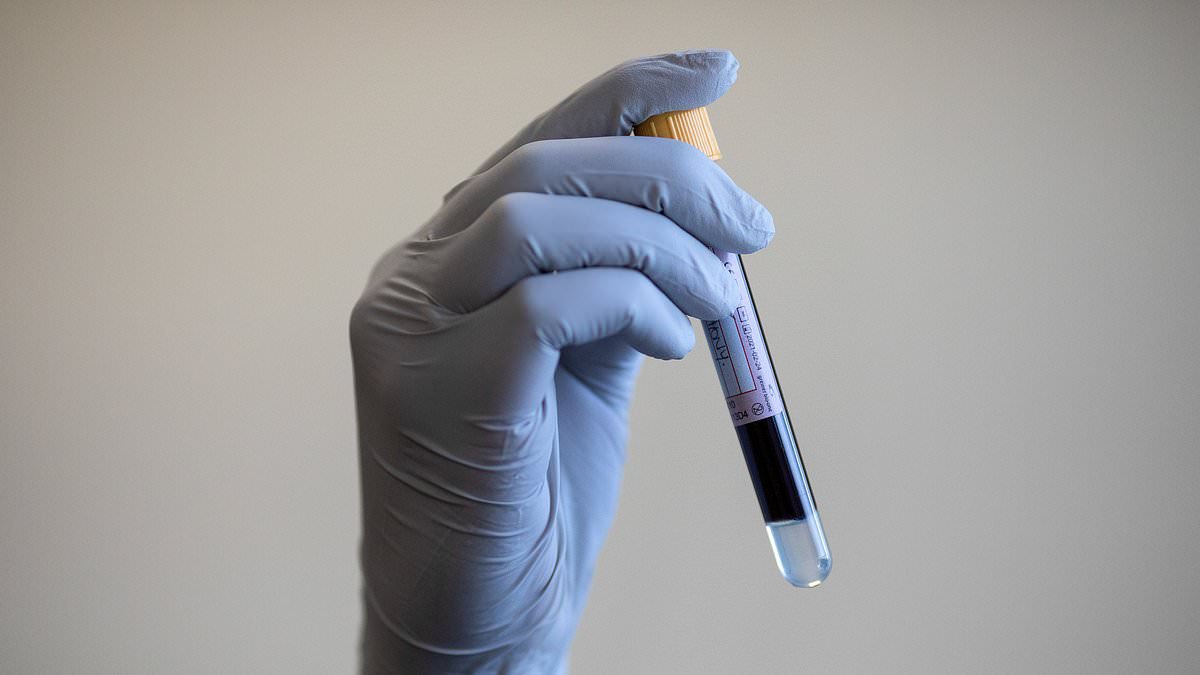

A simple blood test could predict Parkinson’s up to seven years before symptoms appear, marking a ‘major step forward’ in diagnosis.

The disease is a condition in which parts of the brain become progressively damaged, leading to tremor, slowness of movement and memory problems.

There is currently no cure, but experts believe earlier diagnosis would help in finding treatments that could slow or even stop the disease.

The new test uses artificial intelligence (AI) to predict the chances someone will develop Parkinson’s, which is caused by the death of nerve cells in the part of the brain that controls movement.

When these nerve cells die or become damaged, they lose the ability to create an important chemical called dopamine.

The test works by looking for eight proteins in the blood which have been linked to the disease. Tests on 72 people found it was able to detect the likelihood that someone would go on to develop Parkinson’s with 100 per cent accuracy, and up to seven years before the onset of any symptoms

Knowing the symptoms of Parkinson’s can lead to earlier diagnoses and access to treatments that improve patients’ quality of life

People with Parkinson’s are currently treated with dopamine replacement therapy, which can help to maintain quality of life as long as possible.

But it is thought earlier diagnosis and treatment could help protect the dopamine-producing brain cells, preventing symptoms from appearing in the first place.

Senior author Professor Kevin Mills, of University College London (UCL) Great Ormond Street Institute of Child Health, said: ‘As new therapies become available to treat Parkinson’s, we need to diagnose patients before they have developed the symptoms.

‘We cannot regrow our brain cells and therefore we need to protect those that we have.

‘At present we are shutting the stable door after the horse has bolted and we need to start experimental treatments before patients develop symptoms.’

The test works by looking for eight proteins in the blood which have been linked to the disease.

Tests on 72 people found it was able to detect the likelihood that someone would go on to develop Parkinson’s with 100 per cent accuracy, and up to seven years before the onset of any symptoms.

Co-first-author Dr Michael Bartl, of University Medical Centre Goettingen, and Dr Jenny Hallqvist, also from UCL, said: ‘By determining eight proteins in the blood, we can identify potential Parkinson’s patients several years in advance.

‘This means that drug therapies could potentially be given at an earlier stage, which could possibly slow down disease progression or even prevent it from occurring.’

Professor David Dexter, director of research at Parkinson’s UK, which co-funded the research, said: ‘This research represents a major step forward in the search for a definitive and patient-friendly diagnostic test for Parkinson’s.

‘Finding biological markers that can be identified and measured in the blood is much less invasive than a lumbar puncture, which is being used more and more in clinical research.’

The team said that, with sufficient funding, it is hoped the test will be used by the NHS within two years.

They suggest that with further research, this test could potentially distinguish between Parkinson’s and other conditions that have some early similarities.

Around 153,000 people in the UK are already living with Parkinson’s, and it is the world’s fastest-growing neurodegenerative disorder.

The research was published in the journal Nature Communications.