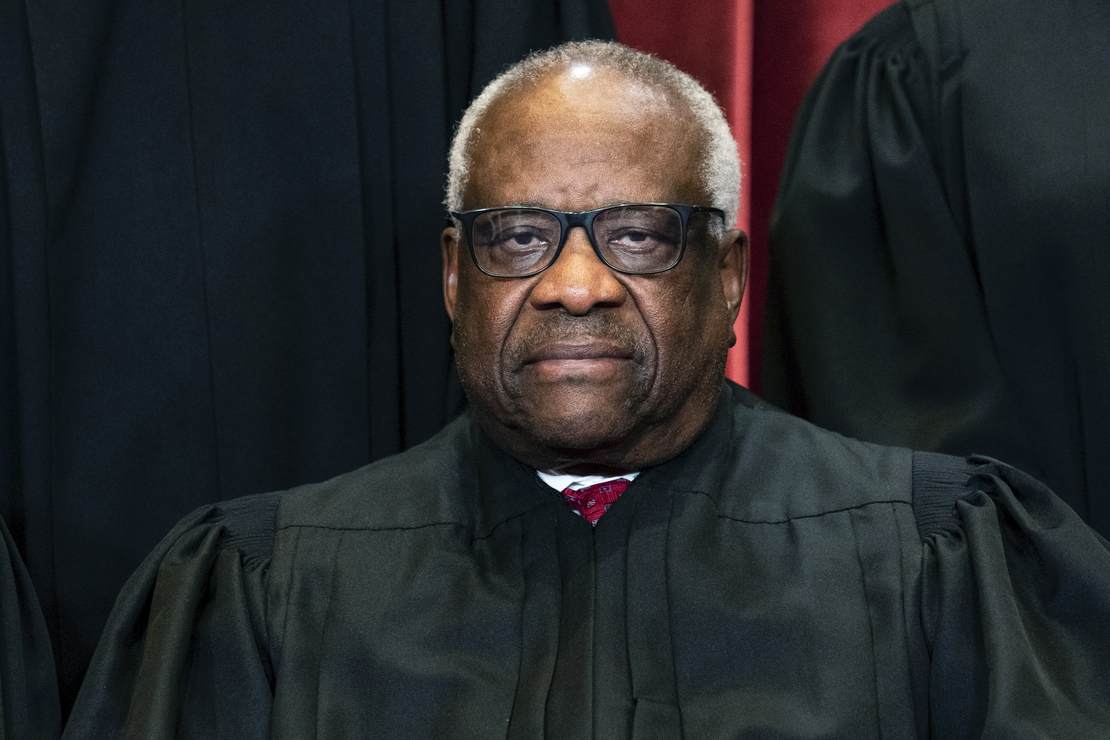

“You begin to look over your shoulder,” Clarence Thomas told a conference audience in Dallas, and he’s not talking about the protesters at the houses of his fellow justices. The most senior Supreme Court justice spoke openly about the impact of the leak on the court itself, especially about the erosion of trust it has created between the jurists and their teams. Thomas’ blunt assessment of the current environment contrasted sharply with Samuel Alito’s demurral a day before.

It’s almost like the end of a marriage, Thomas told the audience at the Old Parkland Conference — like someone cheated but hasn’t quite ‘fessed up:

“What happened in the court is tremendously bad,” Thomas declared in Dallas at a conference organized by the conservative American Enterprise Institute, the Manhattan Institute and the Hoover Institution.

“Look where we are, where now that trust or that belief is gone forever,” he said.

“When you lose that trust, especially in the institution that I’m in, it changes the institution fundamentally. You begin to look over your shoulder. It’s like kind of an infidelity that you can explain … but you can’t undo it.”

One can only imagine what that’s like in a marriage of nine people — or really 45, if you count all of the clerks employed by the nine justices as well. There are others who might have had access to the draft opinion by Alito on Dobbs, such as office staff, security, and custodial personnel. However, it seems highly unlikely that anyone outside the justices themselves and their clerks could have purloined a draft opinion. Thomas has served on the court longest, just over 30 years, and would feel that betrayal perhaps worst of all.

Thomas was less concerned about his personal feelings than the damage the leak has done to the institution. Constitutional institutions and norms are under assault, Thomas warned, and he worried what kind of country we would have left once those get completely hollowed out:

“I wonder how long we’re going to have these institutions at the rate we’re undermining them, and then I wonder when they’re gone or they are destabilized what we will have as a country. I don’t think the prospects are good if we continue to lose them,” Thomas warned.

And Thomas suggested that the present court has already gotten impacted by that erosion. While fondly recalling the relationships between colleagues of his earlier days on the court, Thomas took a not-so-veiled shot at the present line-up:

Thomas also answered a few questions from the audience, including one from a man who asked about the friendships between liberal and conservative justices on the court, such as a well-known friendship between the late liberal Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg and the late conservative Justice Antonin Scalia. “How can we foster that same type of relationship within Congress and within the general population?” the man asked.

“Well, I’m just worried about keeping it at the court now,” Thomas responded. He went on to speak in glowing terms about former colleagues. “This is not the court of that era,” he said.

Thomas did manage to take a swipe at the protesters as well, suggesting that they were immature children rather than serious voices on public policy and the law. He also noted that conservatives never acted out in that manner despite decades of setbacks at the Supreme Court:

READ RELATED: China's endless lockdowns remind some of the Mao era

Thomas also touched in passing on the protests by liberals at conservative justices’ homes in Maryland and Virginia that followed the draft opinion’s release. Thomas argued that conservatives have never acted that way.

“You would never visit Supreme Court justices’ houses when things didn’t go our way. We didn’t throw temper tantrums. I think it is … incumbent on us to always act appropriately and not to repay tit for tat,” he said.

And why is that? The cause, as Alito deduced in his brilliant Dobbs draft, is Roe itself. By usurping the right of the people to deal with an issue that clearly has no relation to the constitutional text, Roe has warped both the legislative and judicial functions of the American form of self-governance for the last 50 years:

Roe was on a collision course with the Constitution from the day it was decided, and Casey perpetuated its errors, and the errors do not concern some arcane corner of the law of little importance to the American people. Rather, wielding nothing but “raw judicial power,” the Court usurped the power to address a question of profound moral and social importance that the Constitution unequivocally leaves for the people. Casey described itself as calling both sides of the national controversy to resolve their debate, but in doing so, Casey necessarily declared a winning side. Those on the losing side-those who sought to advance the state’s interest in fetal life could no longer seek to persuade their elected representatives to adopt policies consistent with their views. The Court short-circuited the democratic process by closing it to the large number of Americans who dissented in any respect from Roe. “Roe fanned into life an issue that has inflamed our national politics in general, and has obscured with its smoke the selection of Justices to this Court in particular, ever since.” Casey, 505 U. S., at 995-996 (Scalia, J., concurring in part and dissenting in part). Together, Roe and Casey represent an error that cannot be allowed to stand. …

When the Court summarized the basis for the scheme it imposed on the country, it asserted that its rules were “consistent with” the following: (1) “the relative weights of the respective interests involved,” (2) “the lessons and examples of medical and legal history,” (3) the lenity of the common law,” and (4) “the demands of the profound problems of the present day.” Put aside the second and third factors, which were based on the Court’s flawed account of history, and what remains are precisely the sort of considerations that legislative bodies often take into account when they draw lines that accommodate competing interests. The scheme Roe produced looked like legislation, and the Court provided the sort of explanation that might be expected from a legislative body.

And Casey made it worse, Alito insisted:

The Casey plurality “call[ed] the contending sides of a national controversy to end their national division,” and claimed the authority to impose a permanent settlement of the issue of a constitutional abortion right simply by saying that the matter was closed. That unprecedented claim exceeded the power vested in us by the Constitution. As Hamilton famously put it, the Constitution gives the judiciary “neither Force nor Will.” Our sole authority is to exercise “judgment” — which is to say, the authority to judge what the law means and how it should apply to the case at hand. The Court has no authority to decree that an erroneous precedent is permanently exempt from evaluation under traditional stare decisis principles. A precedent of this Court is subject to the usual principles of stare decisis under which adherence to precedent is the norm but not an inexorable command. If the rule were otherwise, erroneous decisions like Plessy and Lochner would still be the law. That is not how stare decisis operates.

The Casey plurality also misjudged the practical limits of this Court’s influence. Roe certainly did not succeed in ending division on the issue of abortion. On the contrary, Roe “inflamed” a national issue that has remained bitterly divisive for the past half-century. See Casey, 505 U.S., at 995 (Scalia, J., dissenting); see also R.B. Ginsburg, Speaking in a Judicial Voice, 67 N.Y.U. L. Rev. 1185, 1208 (1992) (Roe may have “halted a political process,” “prolonged divisiveness,” and “deferred stable settlement of the issue.”). And for the past 30 years, Casey has done the same.

Neither decision has ended debate over the issue of a constitutional right to obtain an abortion. Indeed, in this case, 26 States expressly ask us to overrule Roe and Casey and to return the issue of abortion to the people and their elected representatives. This Court’s inability to end debate on the issue should not have been surprising. This Court cannot bring about the permanent resolution of a rancorous national controversy simply by dictating a settlement and telling the people to move on. Whatever influence the Court may have on public attitudes must stem from the strength of our opinions, not an attempt to exercise “raw judicial power.”

Alito and his four concurring colleagues wanted to return the court to its proper constitutional role. Whoever leaked the draft wanted to burn the institution to the ground rather than debate this issue in its proper venue — the legislatures. Not only does that vindicate Alito’s argument, it also tends to make Thomas’ warnings about institutional erosion look prophetic.

We may see a decision on Dobbs as soon as Monday, thanks to a notable surprise addition of that date as a decision day for the Supreme Court. The sooner this Band-Aid gets ripped off, the better.

Source: