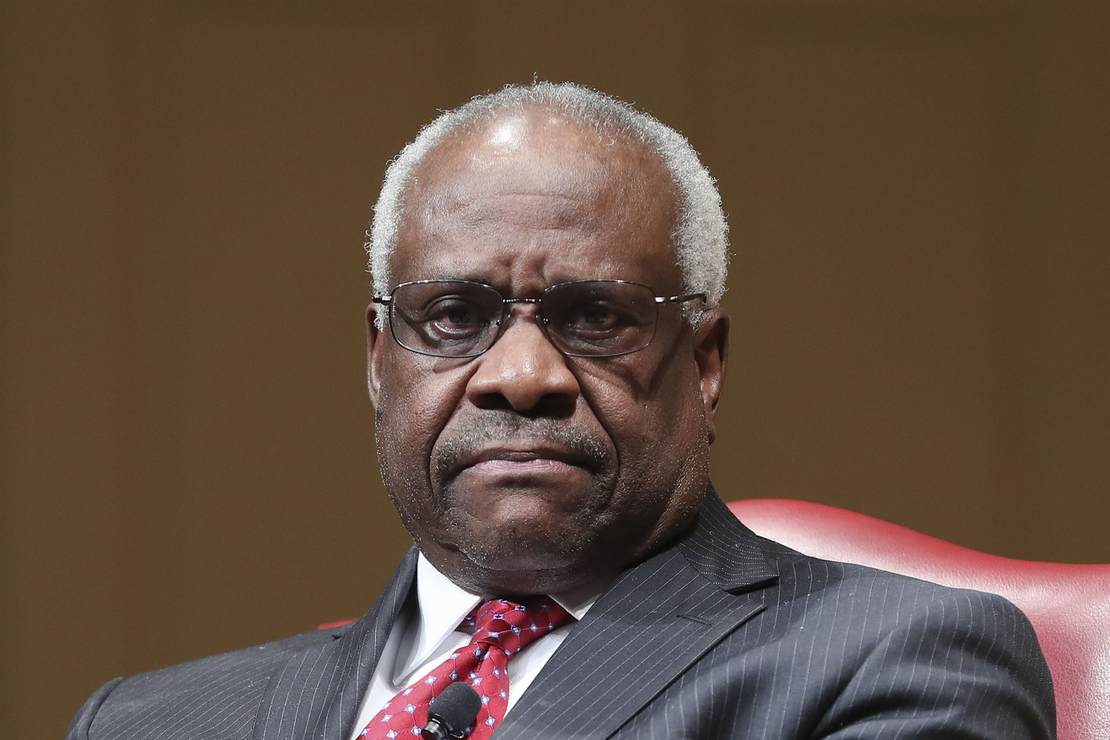

On the twelfth of never, apparently, although perhaps it should. Normally, the Supreme Court’s orders list doesn’t attract much attention, especially at the end of a term when blockbuster cases tend to congregate. Today, for instance, we had Kennedy v Bremerton which finally undid the Lemon standard on Establishment Clause cases. Friday brought us the long-awaited striking down of Roe v Wade, and on Thursday Justice Clarence Thomas himself ended “may issue” permit laws in NYSRPA v Bruen.

Today, however, a denial of cert in a defamation case brought a brief but pointed dissent from Thomas. In Coral Ridge v Southern Poverty Law Center (SPLC), a Christian ministry sued over the SPLC designation of their organization as a “hate group,” which denied them access to donations through Amazon’s charitable designation program, AmazonSmile. The SPLC rebutted the lawsuit on two main points: first, their designation is a First Amendment-protected expression of opinion, and two, Coral Ridge is a “public” entity under the NYT v Sullivan precedent. Coral Ridge conceded the latter in this case but still claimed it could meet the “actual malice” standard.

The court declined to take up the case, but Thomas disagreed, wanting an opportunity to finally address Sullivan. But was this the case by which to challenge it? Maybe …

SPLC responded that its “hate group” designation was protected by the First Amendment. The District Court agreed and dismissed Coral Ridge’s complaint for failure to state a claim. Because Coral Ridge conceded that it was a “‘public figure,’” the court observed that Coral Ridge had to prove three elements to rebut SPLC’s First Amendment defense: the “‘hate group’” designation had to be (1) provably false, (2) actually false, and (3) made with “‘actual malice.’” 406 F. Supp. 3d, at 1270. The court concluded that SPLC’s “hate group” designation was not provably false because “‘hate group’ has a highly debatable and ambiguous meaning.” Id., at 1277. Additionally, the court held that Coral Ridge had not plausibly alleged that SPLC acted with “actual malice,” as defined by this Court’s decision in New York Times Co. v. Sullivan, 376 U. S. 254, 280 (1964). See 406 F. Supp. 3d, at 1278–1280.

The Court of Appeals affirmed but rested its decision exclusively on the “actual malice” standard. See 6 F. 4th 1247, 1251–1253 (CA11 2021). While a defamed person must typically prove only “a false written publication that subjected him to hatred, contempt, or ridicule,” McKee v. Crosby, 586 U. S. ___, ___ (2019) (THOMAS, J., concurring in denial of certiorari) (slip op., at 6) (internal quotation marks omitted), a “public figure” laboring under the “actual malice” standard must prove that a defamatory statement was made “with knowledge that it was false or with reckless disregard of whether it was false or not,” New York Times, 376 U. S., at 280. Applying that “actual malice” standard, the Court of Appeals agreed that Coral Ridge’s complaint had not sufficiently alleged that SPLC doubted or had good reason to doubt the truth of its “hate group” designation. See 6 F. 4th, at 1252–1253.

That may have been the only point considered by the Court of Appeal, but the district court apparently also ruled that the plaintiffs hadn’t established that the statement was “provably false” either. That applies ahead of the “actual malice” requirement for public persons/entities, obviously. If the statement isn’t provably false, then the question of malice is moot. The better question here might be whether SPLC’s designation of Coral Ridge as a “hate group” really functions as mere opinion, given its connection to commercial entities such as Amazon. SPLC plays very fast and loose with that designation, applying it liberally to people and entities who opposes same-sex marriage and other parts of the LGBTQ agenda regardless of motivation and apparently regardless of activist actions.

A challenge on that basis would be verrrryyy interesting. To me and Clarence Thomas, anyway. Apparently, the other justices don’t seem interested in that question, nor in the question Thomas raises here:

I would grant certiorari in this case to revisit the “actual malice” standard. This case is one of many showing how New York Times and its progeny have allowed media organizations and interest groups “to cast false aspersions on public figures with near impunity.” Tah, 991 F. 3d, at 254 (opinion of Silberman, J.). SPLC’s “hate group” designation lumped Coral Ridge’s Christian ministry with groups like the Ku Klux Klan and Neo-Nazis. It placed Coral Ridge on an interactive, online “Hate Map” and caused Coral Ridge concrete financial injury by excluding it from the AmazonSmile donation program. Nonetheless, unable to satisfy the “almost impossible” actual-malice standard this Court has imposed, Coral Ridge could not hold SPLC to account for what it maintains is a blatant falsehood.

This is not a new argument from Thomas, of course. Three years ago, Thomas urged the court to find a way to vacate the Sullivan standard and allow an even playing field for both public and private persons in defamation actions. That case involved a lawsuit against Bill Cosby which Thomas agreed to refuse at a particular stage, but wrote extensively on why he thought the Sullivan court had turned defamation law and history on its head:

Far from increasing a public figure’s burden in a defamation action, the common law deemed libels against public figures to be, if anything, more serious and injurious than ordinary libels. See 3 Blackstone *124 (“Words also tending to scandalize a magistrate, or person in a public trust, are reputed more highly injurious than when spoken of a private man”); 4 id., at *150 (defining libels as “malicious defamations of any person, and especially a magistrate, made public by either printing, writing, signs, or pictures, in order to provoke him to wrath, or expose him to public hatred, contempt, and ridicule” (emphasis added)). Libel of a public official was deemed an offense “‘most dangerous to the people, and deserv[ing of] punishment, because the people may be deceived and reject the best citizens to their great injury, and it may be to the loss of their liberties.’” …

READ RELATED: Seriously? Biden looks at releasing the last diesel reserves

The common law did afford defendants a privilege to comment on public questions and matters of public interest. Starkie *237–*238. This privilege extended to the “public conduct of a public man,” which was a “matter of public interest” that could “be discussed with the fullest freedom” and “made the subject of hostile criticism.” Id., at *242. Under this privilege, “criticism may reasonably be applied to a public man in a public capacity which might not be applied to a private individual.” Ibid. And the privilege extended to the man’s character “‘so far as it may respect his fitness and qualifications for the office,’” which was in the interest of the people to know. White, supra, at 290 (quoting Clap, supra, at 169).

But the purposes underlying this privilege also defined its limits. Thus, the privilege applied only when the facts stated were true. Starkie *238, n. 4; White, supra, at 290. And the privilege did not afford the publisher an opportunity to defame the officer’s private character. …

New York Times and the Court’s decisions extending it were policy-driven decisions masquerading as constitutional law. Instead of simply applying the First Amendment as it was understood by the people who ratified it, the Court fashioned its own “‘federal rule[s]’” by balancing the “competing values at stake in defamation suits.” Gertz, supra, at 334, 348 (quoting New York Times, supra, at 279).

We should not continue to reflexively apply this policy-driven approach to the Constitution. Instead, we should carefully examine the original meaning of the First and Fourteenth Amendments. If the Constitution does not require public figures to satisfy an actual-malice standard in state-law defamation suits, then neither should we.

One year ago, it appeared that Thomas had convinced Neil Gorsuch to join this quest. In Berisha v Lawson, both Thomas and Gorsuch dissented on a denial of cert in a case that might have been better suited for such a review. Guy Lawson wrote a book purporting to be the “true story” of international arms dealers, a book that fingered Shkelzen Berisha as a member of the Albanian “mafia.” (The book was made into the film War Dogs with Jonah Hill and Miles Teller.) While Thomas largely raised the same and still compelling issues as he had in the 2019 case, Gorsuch made an argument that Sullivan has perverted incentives so much that it might be better for publications to not bother with fact-checking at all:

But over time the actual malice standard has evolved from a high bar to recovery into an effective immunity from liability. Statistics show that the number of defamation trials involving publications has declined dramatically over the past few decades: In the 1980s there were on average 27 per year; in 2018 there were 3. Logan 808–810 (surveying data from the Media Law Resource Center). For those rare plaintiffs able to secure a favorable jury verdict, nearly one out of five today will have their awards eliminated in post-trial motions practice. Id., at 809. And any verdict that manages to make it past all that is still likely to be reversed on appeal. Perhaps in part because this Court’s jurisprudence has been understood to invite appellate courts to engage in the unusual practice of revisiting a jury’s factual determinations de novo, it appears just 1 of every 10 jury awards now survives appeal. Id., at 809–810.

The bottom line? It seems that publishing without investigation, fact-checking, or editing has become the optimal legal strategy. See id., at 778–779. Under the actual malice regime as it has evolved, “ignorance is bliss.” Id., at 778. Combine this legal incentive with the business incentives fostered by our new media world and the deck seems stacked against those with traditional (and expensive) journalistic standards—and in favor of those who can dissemi nate the most sensational information as efficiently as possible without any particular concern for truth. See ibid. What started in 1964 with a decision to tolerate the occasional falsehood to ensure robust reporting by a comparative handful of print and broadcast outlets has evolved into an ironclad subsidy for the publication of falsehoods by means and on a scale previously unimaginable. Id.,at 804. As Sullivan’s actual malice standard has come to apply in our new world, it’s hard not to ask whether it now even “cut[s] against the very values underlying the decision.” Kagan, A Libel Story: Sullivan Then and Now, 18 L. & Soc. Inquiry 197, 207 (1993) (reviewing A. Lewis, Make No Law: The Sullivan Case and the First Amendment (1991)). If ensuring an informed democratic debate is the goal, how well do we serve that interest with rules that no longer merely tolerate but encourage falsehoods in quantities no one could have envisioned almost 60 years ago?

The Internet and its vast democratization of media, while good overall, makes Sullivan even less sustainable, Gorsuch also argued last year:

Again, it’s unclear how well these modern developments serve Sullivan’s original purposes. Not only has the doctrine evolved into a subsidy for published falsehoods on a scale no one could have foreseen, it has come to leave far more people without redress than anyone could have predicted. And the very categories and tests this Court invented and instructed lower courts to use in this area—“pervasively famous,” “limited purpose public figure”—seem increasingly malleable and even archaic when almost anyone can attract some degree of public notoriety in some media segment. Rules intended to ensure a robust debate over actions taken by high public officials carrying out the public’s business increasingly seem to leave even ordinary Americans without recourse for grievous defamation. At least as they are applied today, it’s far from obvious whether Sullivan’s rules do more to encourage people of goodwill to engage in democratic self-governance or discourage them from risking even the slightest step toward public life.

This argument in particular resonates with the cert application for Coral Ridge v SPLC. It seems curious why Gorsuch didn’t join Thomas in dissent here as well; perhaps Gorsuch decided that the lack of a provable falsehood made it a poor test case. That may well be a good choice, but I find myself getting closer to Thomas’ position than I was three years ago, via Gorsuch’s arguments in his Berisha dissent. It’s time for the Supreme Court to revisit Sullivan in light of the massive changes in the media over the last six decades, not to mention the way in which nearly anyone can find themselves declared a “public person” and stripped of their ability to seek justice for defamation.

Source: